A difficult start: the economic sciences in the nineteenth century

Though the economic sciences at the University of Basel may not be as old as law, theology, medicine, or most of the humanities, they do a have significantly longer history than the newer social sciences. The first chair in economics was established in 1855, dedicated to “national economy and statistics.”

At most German and Swiss universities, such as Bern, Lausanne, and Fribourg, economics developed as part of the Faculty of Law. This was not the case in Basel. Here, the Faculty of Law in the mid-nineteenth century was not particularly enthusiastic about the new discipline. Consequently, the new chair was assigned to the Faculty of Philosophy. Compared to older disciplines such as philosophy or history, both of which had been taught in Basel for several centuries, economics remained a somewhat neglected specialty within the Faculty of Philosophy for the next one and a half centuries, despite several attempts at reform. Although the transfer of economics to the Faculty of Law was discussed in 1905 and again in the 1920s, its members resisted the move on both occasions. The legal scholars could not relate to the methodological and theoretical profile of economics, and so they also hindered any greater integration of economic sciences into the legal curriculum. Likewise, the plan to make economics the core of a new Faculty of State Sciences (Staatswissenschaften) failed in the 1920s, as the university could not provide the necessary additional funds. Economics thus remained marginal in university studies until the First World War. Within the Faculty of Philosophy, the discipline received little attention, while no external support was forthcoming from the Faculty of Law. Courses in economic sciences were neither compulsory nor covered by exams in legal studies.

Challenging beginnings

The early decades of the discipline’s history were not auspicious. The problems began even before the first appointment was made. The older, highly traditional faculty members largely rejected economics, though it did find some advocates among the younger professors. In addition, the expectations placed on the figure appointed to the new chair were high. He was not only to prove himself academically but also to be capable of communicating the subject to a broader, urban public. Specifically, he was expected to teach at the Basel Trade School and to take on an active role as a public speaker. This demand – to not only pursue economic sciences academically but also to bring them closer to a bourgeoisie in Basel defined by commerce and education – remained closely linked to academic teaching well into the twentieth century. The university’s oversight Committee, or Kuratel – still an institution dominated by academics, despite city involvement – accordingly praised the candidate appointed in 1855, the Bonn economist Erwin Nasse (1829–1890), for showing no interest in “theoretical exaggerations, figments, and follies.” Yet the new discipline met with little interest among Basel students: only one student enrolled for Nasse’s inaugural lecture. Clearly disappointed with the prospects in Basel, Nasse, who later became a cofounder and chairman of the Association for Social Policy, returned to Germany after one semester to accept a position at the University of Rostock.

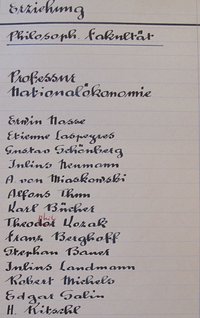

The structural problems of teaching in economic science persisted for decades, turning the Basel chair of economics into a kind of stepping-stone for a career elsewhere. It was primarily younger German professors – the first Swiss professor was not appointed until 1942, and as of 2010, the field in Basel was still waiting for a full professorship to be held by a woman – who made their mark as young scholars, while aiming for a better position and leaving Basel as soon as possible. After Nasse’s departure, the chair remained vacant for eight years. Subsequently, over a period of thirty-five years (1864 to 1899), no fewer than eight economists were appointed, most of whom left the chair after two to three years.