University sites

Since its founding, the University of Basel has been spread across various sites and buildings. Originally located on Cathedral Hill and the Rheinsprung, the university later expanded toward St. Peter’s Square, Hebel Street, and the Schällemätteli neighborhood. The dynamic growth during the twentieth century makes it difficult to keep track of the current building stock: in 2010, the University of Basel had operations at around forty locations in over ninety properties.

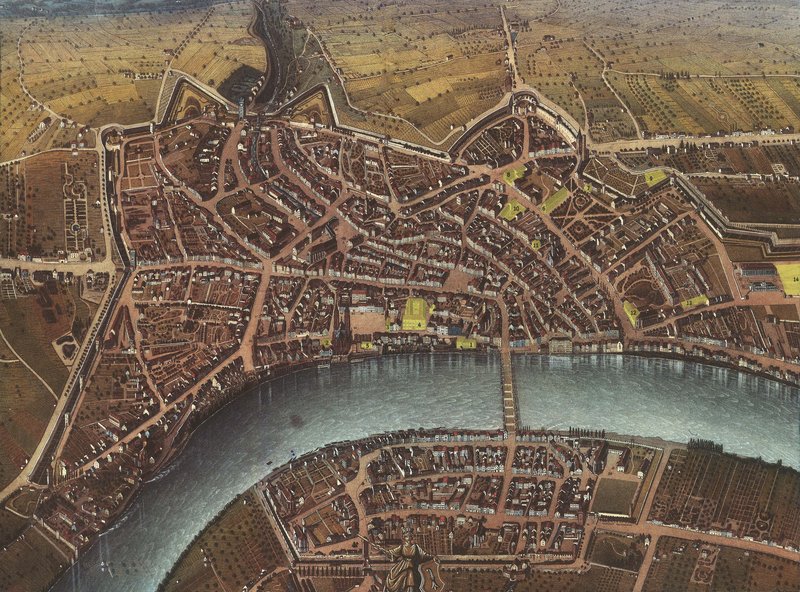

The University of Basel has occupied many, constantly changing, sites. These pages present the history of the University of Basel in its spatial dimension – as a topography documenting and tracking the university’s buildings, sites, and spaces. This mental map of how university spaces have been continuously relocated reflects how the university has responded to a shifting landscape of sciences, the differentiation of academic disciplines, changing enrollments, and shifts in the university’s relationship with the city – just as these aspects of the university’s history have responded to changes, some of them quite turbulent, in Basel’s architectural fabric. Over 550 years of spatial history, two constants have prevailed: the university never had just “one site” and its space has always been closely intertwined with that of the city.

The list of the sites occupied by the University of Basel since its founding is long and remarkable. Buildings such as the Lower College in the university’s first centuries, and more recently the Kollegienhaus on St. Peter’s Square, have periodically taken on certain central functions. But Basel lacks a single main building symbolically representing the entire university. Its various departments (institutes and seminars), libraries, research institutions, and teaching spaces have been housed in different buildings, often changing across centuries; the spaces of the university have been in constant flux, while remaining closely linked to the space of the city.

The path taken by the university and its disciplines from its founding to its anniversary year can also be told as the history of many individual buildings. Only rarely did the university and the City of Basel construct new buildings for academic use; more often, existing structures were appropriated by being purchased, rented, repurposed, or modified. This history of university space is a history of spatial expansion, but not a history of progress following any linear trajectory. It has manifested as a sequence of construction sites, relocations, and ever-changing building uses.

Some broad trends can nevertheless be discerned in the history of how the university has used its space. A bird’s eye view shows how the topography of the university locations has shifted over time.

Over the first three hundred years of the university’s existence, its daily life played out on Cathedral Hill between the Lower College on the Rheinsprung and the Upper College on Augustiner Street, in the cathedral itself, and in many neighboring buildings. The new museum building, constructed in 1849 to replace the Upper College, initiated a period of spatial expansion and intense university and urban construction, while also marking the departure from Cathedral Hill.

In the nineteenth century, the university’s center moved to the city’s former periphery in the west. In quick succession, the new hospital, the Bernoullianum, the Vesalianum, and the University Library were built: representative functional buildings for university use, financed by the city and a philanthropic citizenry. The once suburban area officially became the university’s focal point with the construction of the Kollegienhaus in 1939.

In the twentieth century, the university continued to grow – and additional topographical concentrations emerged. The natural sciences shifted to the St. Johann district with a series of new construction projects, and the humanities formed a kind of satellite belt around St. Peter’s Square, spread over numerous smaller sites.

Many factors drove these developments – with strategic spatial planning, which might have allocated space to new disciplines based on their scientific dynamics and political significance, perhaps playing the smallest role. Conversely, it seems that some new construction projects promoted the development of various disciplines rather than the other way around. Some decision-making processes, such the construction of the Kollegienhaus on St. Peter’s Square, took generations – this formation process of new university space proved highly complex and involved a variety of actors: university and city officials with diverse interests; the engagement of Basel’s citizenry, which could make or break construction projects; political circumstances such as the cantonal separation, which affected the university’s financial and spatial situation; legal conditions such as regulations on building stock in the University Act; substantial financial support from the Voluntary Academic Society, enabling major construction projects from 1874; the internal dynamics in the development of disciplines and scientific areas of focus; and the number of students, which would rise from around 1,000 to more than 10,000 over the course of the twentieth century.

More recently, the process of spatial development at the university has been guided and focused by more comprehensive strategic spatial planning, which has sought to realize a model conception of the university within the city as a vision of various campus areas. The anniversary year of 2010 saw the Faculty of Business and Economics and the Faculty of Law occupying locations near the train station, the natural sciences soon to be relocated further west, and humanities and social sciences departments and units expecting to be concentrated around St. Peter's Square.

There has always been close integration of university spaces and sites into the city’s topography – even current plans to realize a new campus concept built around several centers envision a “university within the city.” “Concentration,” “densification,” and “visibility” are the guiding principles of the university’s strategic spatial planning. Yet however they take shape, the future plans for the university’s campus will remain part of the city, integrated into its urban fabric.