Ten stained-glass windows – university self-presentation

In 1559/60, one hundred years after the University of Basel was founded, the new library, known as the Brabeuterium, was inaugurated on the Rheinsprung. To mark this event, ten stained-glass windows were donated, providing a means for the university and its members to present themselves.

Such donations were entirely customary for building inaugurations at the time and were a popular form of self-presentation. Most of the heraldic windows were created by Ludwig Ringler, a renowned Basel glass painter, and Hans Jörg Riecher, perhaps less notable.

The window with the rector’s coat of arms symbolizes the entire university, while each of the four faculties also contributed their own windows. However, only the draft design of the window for the Faculty of Law has survived. Additionally, individual professors, deputies, and librarians each donated their own windows.

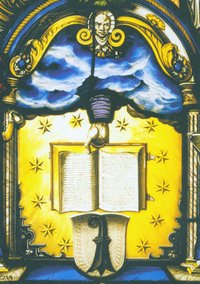

The university’s heraldic window

The scrollwork cartouche in the base reads: “EX DONO ALMAE UNIVERSITATIS STUDII BASILIENSIS 1560” (Gift of the University of Basel 1560).

In the main section, the open book, offered from the clouds by a hand and surrounded by twelve stars, corresponds to the rector’s seal, which had been in use since 1460. In iconology, the right hand of God stands for blessing, admonition, or guidance, possibly symbolizing in this context the giving of the tablets of the law to Moses. The four spandrels feature allegorical figures representing the four faculties, dressed in antique fashion: Medicina with a raised glass vessel (possibly a urinal glass), Philosophia holding a tablet with arithmetic calculations, Theologia writing at a marble table before a cross, and Iustitia with a scepter and sword.

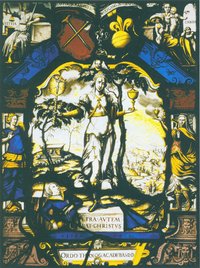

The stained-glass panel of the Faculty of Theology

The inscription on the base of the cartouche reads: “ORDO THEOLOG. ACADE. BAS. D(ONO) D(DEDIT)” (Gift from the Faculty of Theology at the Basel Academy). The main field of the panel shows a woman in ancient-style muscle armor, symbolizing the victorious, true, Evangelical Church of Christ. Holding a flaming crucifix in her right hand and a covered chalice in her left, she also carries a closed book under her arm. She stands on a stone block inscribed “PETRA AUTEM ERAT CHISTUS” (The rock was Christ, 1 Cor. 10:4). Behind the stone lies a woman representing the fallen Roman Church, with a discarded chalice and rosary. The background opens to a landscape symbolizing Christ’s sacrifice and its ritual reenactment in worship. To the right, along a river, several haloed figures, likely apostles, are depicted spreading the Good News after Christ’s death. The allegorical figures represent faith, love, hope, and justice. The coats of arms of theologians Martin Borrhaus and Wolfgang Wissenburg are displayed at the top of the arch. t.

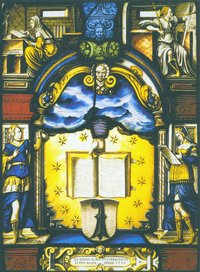

The design of the stained-glass panel for the Faculty of Law

The stained-glass panel for the Faculty of Law has not survived, but the preliminary drawing has. To the left of Basel’s coat of arms stands the pope, identified by the symbol of a key, and to the right, the emperor, holding an orb and a drawn sword; these figures embody canon and civil law. The faculty retained this imagery from its fifteenth-century seal, even after the Reformation. At the top of the image, Iustitia is depicted on a globe with Veritas and Prudentia. Iustitia, wearing a blindfold, holds scales and a sword, symbolizing earthly justice. Veritas is shown reading from a book, while Prudentia looks at her reflection. The three unfinished shields likely contained the names of three faculty members.

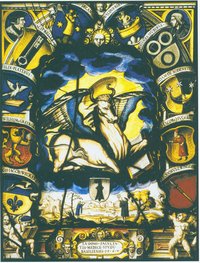

The stained-glass panel of the Faculty of Medicine

The scrollwork cartouche in the base reads: “EX DONO FACVLTATIS MEDICE STVDY BASILIENSIS 1560” (Gift from the Faculty of Medicine). The main image, referencing the fifteenth-century faculty seal, features the winged and haloed ox of Luke, the Evangelist and patron saint of doctors. In the foreground, two individuals are conducting scientific observations before a landscape with a city. An academic, dressed in robes and a cap, holds an armillary sphere and gestures toward the sky. Across from him, at some distance, a student (?) uses a simple protractor to measure buildings in the landscape. These actions, though not directly related to medicine, can be seen as representations of knowledge or the understanding of reality, reflecting the field’s view of itself. The surrounding arch is adorned with ten shields representing faculty members teaching in 1560.

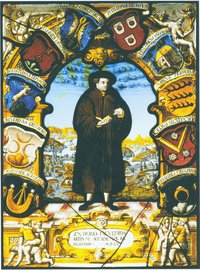

The stained-glass panel of the Faculty of Liberal Arts

The scrollwork cartouche in the base reads: “EX DONO FACVLTATIS ARTIVM ACCADEMIAE BASILIENSIS MDLX” (Gift from the Faculty of Liberal Arts, 1560). It depicts a man standing in a brown robe and cap, modeled after Hans Holbein’s famous woodcut of Erasmus of Rotterdam, shown “in a niche” within an arcade frame – thus paying homage to the renowned humanist. The man stands with an open book on a tiled stone floor, with a purely decorative and idealized cityscape featuring bridges, ships, churches, central buildings, and gabled houses behind him. Like the window for the Faculty of Medicine, the surrounding arcade is adorned with ten shields of faculty members.

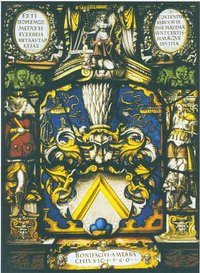

The stained-glass panel of the jurist Bonifacius Amerbach

The base cartouche reads: “BONIFACIVS AMERBACHIVS I(VRIS) C(ONSVLTVS)” (Bonifacius Amerbach, jurist). Notes from Bonifacius Amerbach, detailing the text of the mottos and inscriptions and providing suggestions for the design of individual elements, show a close collaboration between the piece’s intellectual patron and its executing artist. The central panel shows Amerbach’s coat of arms on a blue background. The program of accompanying figures and mottos characterizes the sixty-five-year-old scholar as a contented wise man. This is particularly evident in the mottos on the spandrels: on the left, “ΕΣΤΙ ΠΟΡΙΣΜΟΣ ΜΕΓΑΣ Η ΕΥΣΕΒΕΙΑ ΜΕΤΑ ΑΥΤΑΡΚΕΙΑΣ” (Godliness with contentment is great gain, 1 Tim. 6:6), and on the right, “CONTENTUM REBVS SVIS ESSE MAXIMAE SVNT CERTISSIMAEQVE DIVITIAE” (Being content with what you have is the greatest and most certain wealth, Cicero, Paradoxa). Between these inscriptions sits “ΑΥΤΑΡΚΕΙΑ” (autarky, or self-sufficiency), holding a cornucopia in one hand and an olive branch in the other, with her feet resting on the bound “ΦΙΛΑΡΓΥΡΙΑ” (greed). On the left, “NEMESIS” stands with a bent measuring stick and a bridle, personifying a punishing and just fate, and on the right, “IVSITITA” (justice) holds scales and a fasces, the ancient Roman symbol of authority and office, with a crane at her feet standing on one leg with a stone in its raised claw, a symbol of vigilance.

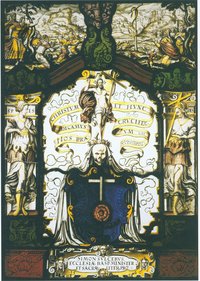

The stained-glass panel of the theologian Simon Sulzer

The scrollwork cartouche in the base reads: “SIMON SVLCERVS ECCLESIAE BASI(LIENSIS) MINISTER ET SACRAR(VM) LITER(ARVM) PRO(FESSOR) 1560” (Servant of the Basel church and professor of theology, 1560). The center shows Sulzer’s coat of arms on a blue field: a rose on a green stem, crowned by a white cross, topped by a skull draped with a shroud. The resurrected Christ stands on the skull, holding a cross and a banner with Sulzer’s motto: “NOS PRAEDICAMVS CHRISTVM ET HVNC CRVCIFIXVM” (We preach Christ crucified, 1 Cor. 1:23). On the left, the allegory “SPES” (hope) is depicted, and on the right, “FIDES” (faith). The nearly monochromatic upper scene shows “Moses and the bronze serpent,” which has been interpreted since medieval times as a foreshadowing of Christ’s atonement.

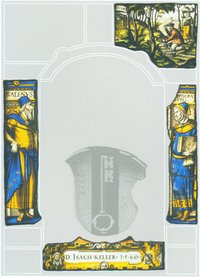

The stained-glass panel of the professor of medicine Isaak Keller

This stained-glass panel has survived only in fragments. The inscription on the base of the cartouche reads: “D(OCTOR) ISACH KELLER 1560.” The lost central panel would have depicted the coat of arms of Isaak Keller, a professor of theoretical medicine, flanked by Galen and Hippocrates. In the upper right spandrel of an arcade, a depiction of a farmer and a farmwoman collecting roots or herbs has survived. Isaak Keller was a notable figure in the university’s history, serving as rector in 1559 and 1569. In 1571, he was appointed as the administrator of the secularized St. Peter’s Chapter. However, in 1579, he was found to have embezzled a significant sum of 31,000 pounds, leading to his immediate removal and expulsion from the Faculty of Medicine. After he fled the city, his property was auctioned. It is unclear whether the panel was accidentally damaged or removed deliberately as part of a “damnatio memoriae.”

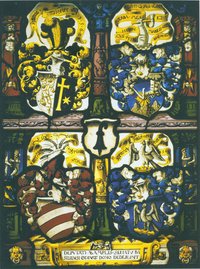

The stained-glass panel of the four deputies of the City Council, 1561/62

To feature the coats of arms of the four deputies of the City Council, this panel uniquely breaks with the format of a central image framed by an arcade, instead creating four sections. A shield with the Basel staff is placed at the crossroads of these divisions. The inscription on the cartouche at the bottom center reads: “DEPVTATI AB AMPLIS(SIMO) SENATV BASILIENSI ORDINATI DONO DEDERVNT” (The deputies appointed by the Grand Council of Basel have given this as a gift). The deputies were responsible for managing the university’s income and served as liaisons between it and the council. This committee, established in 1461, was composed of three council members and the city scribe.

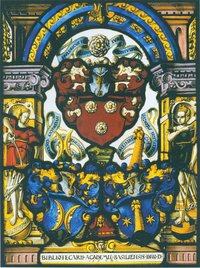

The stained-glass panel of the three librarians, 1564

Donated by three librarians, this stained-glass panel displays their coats of arms in the central section. These include the jurist Ulrich Iselin (“HVLDRICVS ISELIN IVRE CONSVLTVS”), the dean of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ulrich Koch (“HVLDRCVS COCCIVS THEOLOGVS”), and the dean of the medical faculty (“HEINRICVS PANTALEON MEDICVS”). On the left, the allegory “TEMPORA ANT.,” representing the cardinal virtue of moderation – temperance – pours water from a jug into a wine goblet. On the right, also standing on a globe, is the allegory of faith (fides), pointing to the cross she holds with her left arm. A small crescent moon on her forehead may also signify the ancient goddess Diana. The cartouche at the bottom lists the donors as the librarians: “BIBLIOTHECARII ACADEMIE BASILIENSIS DONO D(EDERUNT) 1564.”