A new era of autonomy

When the University of Basel was granted autonomy in January 1996, it was a Swiss first that also attracted international attention. Since then, other Swiss universities have followed suit. On paper, the various regulations may look different, but their overall effect has been a retreat of direct government control everywhere, especially in German-speaking Switzerland. The universities are funded by a global budget approved by canton parliaments, while making decisions themselves about how this money is spent.

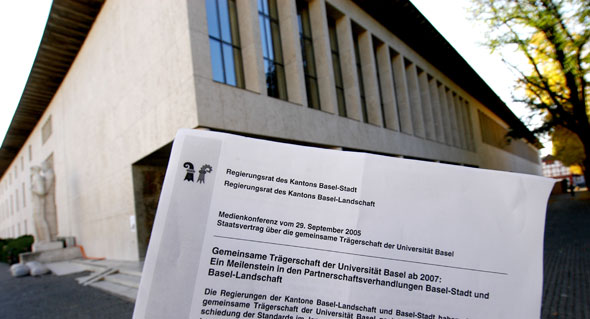

Unique features in Basel

What sets Basel apart is the fact that the presidency of the University Council is not held by a member of the government. The industrialist Rolf Soiron headed the first University Council for almost ten years, from 1995 to 2005. This solution of appointing an outsider eliminated a potential point of conflict between the sponsoring cantons, both of which could have laid claim to the position. Originally, the nine-member University Council included three governmental members: the head of the Basel Department of Health in addition to each canton’s director of education. Following the 2007 agreement between the cantons, which established their full partnership in sponsoring the university, this participation was reduced to the two directors of education. Since 2007, the university has also had the right to nominate one of the nine members for election. The rector and the director of administration have furthermore been nonvoting members of the University Council from the beginning, along with council’s secretary.

High expectations

The move toward autonomy brought high expectations. Much work was left to be done to flesh out the plans for expanding the number of academic subjects and disciplines and overcoming bottlenecks, while the administration was still being set up and a transparent system of financing had yet to be established. In many areas, improvisation was required. The additional funds provided by Basel-Countryside offered only limited relief, given the reduction in services directly provided by Basel-City.

Tight budgets meant the renewal fund created by Basel-Countryside was vital: 10 percent of the canton’s total annual contribution of seventy-five million francs went into this fund, over which the university had direct control. The money was used to implement numerous initiatives, yet it was also clear that over the longer term the expansions or newly created chairs seeded by this fund would have to be included in the regular budget. This was also true, for example, of the program “Mankind-Society-Environment,” which in 2002 ceased to be supported by the renewal fund established by Basel-Countryside.

At the same time, the influence of federal higher education policy increased during these years. The Swiss federal state secretary for education and science had intervened in Basel in 1993, even before reforms got underway, by questioning the future of the pharmaceutical program. Although Basel ultimately retained the program, the intervention forced a restructuring. Additional sources of funding came from other sources within the Swiss Confederation, such as support to advance women’s equality, or from cantons lacking a university, which increasingly began to compensate the university cantons for enrolling their students.

If we further include money secured from the Swiss National Science Foundation or other sources of third-party funding under growing competition between universities, then the University of Basel was in fact able to expand its financial resources despite government pressure to save money during the first years of autonomy. In 1998, an expert from the private sector (Novartis) took over the management of finances and controlling; a similar approach was taken with the management of construction. The first University Council included two representatives from large industrial corporations who promoted such appointments and knew how to arrange the necessary contacts.

An important organizational change was made in 1998, when the model of rotating among three rectors (designated, acting, and emeritus) was replaced by a single rector appointed specifically and exclusively to this position. It was the view of University Council that this would ensure greater continuity and professionalism. Since then, the rector has been assisted by two vice rectors – one for research and development and another for teaching and continuing education, with the latter being held for the first time by a woman, Annetrudi Kress, a member of the Faculty of Medicine and long-time head of the Coordination Commission. The first rector under the new system was the theologian Ulrich Gäbler, who held this position until 2006, when he was succeeded by the Egyptologist Antonio Loprieno.

Forms of autonomy

Since the discussions in the late 1980s, the university’s “autonomy” had become an increasingly explicitly stated goal. The driving force here, however, has not been any principles of “new public management,” but rather the sheer necessity of making it possible for Basel-Countryside to cosponsor the university by freeing it from its close integration into Basel-City. The specific forms in which this goal was realized were nevertheless certainly characterized by the search for greater efficiency typical of the time, and by a desire for a more pronounced focus on business management at the top.

The requirement instituted with this shift that the university prepare detailed reports, and that the service mandate be subject to periodic reapproval, responded to the desire of both cantonal parliaments to maintain some degree of influence over the university’s development. Since the late 1990s, these reports and agreements have exploded in size. The 2006 agreement between the cantons institutionalized an annual discussion between members of the Basel parliaments and university management.

Despite the unmistakable consolidation, the leadership and management system that has emerged at the University of Basel is still evolving. It is proving to be a “mixed system” that can only function if cooperation is ensured through astute appointments in senior management positions. The rector continues to be elected by the Senate, which understands itself as an organ of traditional academic self-governance. Its authority is complemented by the responsibilities of the new supervisory and management bodies, which have grown over time. For example, the University Council possesses a veto in electing the rector, and avoiding such a situation requires all parties to come to an agreement before an election takes place.

Partially as a concession to criticism expressed from within the university in 2002–2004, the 2006 agreement between the cantons also requires the University Council to consult the relevant faculties in making decisions about the strategic direction of the institution or about creating or eliminating degree programs. In addition, the Senate may appoint a member of its own choosing to the University Council. With provisions of this kind, the latest agreement between Basel-City and Basel-Countryside reinforces the integrative features of what has become known as the Basel model, which more or less compels forms of cooperation. These aspects are perhaps what most sets Basel apart.