Psychology on philosophy’s coattails

Seeking a moment from which everything began is a challenging task in the case of psychology at the University of Basel. The field’s origins are not shrouded in darkness but are quite dispersed and neither easily nor clearly recognizable as such. This is because the context in which they are situated differs in many ways from the current context of academic psychology.

While psychology established itself as an independent science in German scientific centers in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, in Basel it remained part of philosophy until the mid-twentieth century. The Basel Philosophical Seminar itself was a late foundation, only realized in 1920, after some 460 years of university operation. In the preceding period, philosophy belonged to the Pedagogical Seminar, and as a philosophical subbranch, psychology had also fit into the institutional framework of pedagogy as a field at the university.

The birth of psychology from a philosophical spirit

Despite these dependencies, psychology soon gained its own significance and thus moved in step with the genesis of European science. The increasing consideration of psychological questions in Basel was closely linked to the establishment of a second, nonstatutory chair of philosophy in 1866. The holder of this professorship was expected not only to teach pedagogy and logic but also to represent psychology in teaching and research.

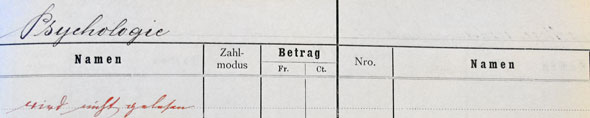

Wilhelm Dilthey, then thirty-three years old, was the first to fill this position in 1867. He left Basel just a year later, however, and his successors likewise failed to remain in the position for long. The philosopher Gustav Teichmüller from Braunschweig, who succeeded Dilthey, moved after two years to Dorpat, then part of the Russian Empire, to achieve broader scientific impact than would have been possible in the academically quaint university in Basel. The scientific prestige that rising academics could acquire in Basel at that time was quite modest – their salary even more so. The division of Basel into two cantons meant that the university still suffered from political uncertainties and financial losses, and institute resources, as well as student numbers, remained far below German standards. Therefore, only very young scholars from Germany accepted appointments to the University of Basel, where they saw their position as nothing more than a stepping-stone toward a more prestigious institution.

Nietzsche’s failed application

There was one German who would have likely been pleased to hold the new chair for a longer period: Friedrich Nietzsche, who had been a professor of Greek language and literature since 1869, applied for the vacant chair after only a year and a half of teaching Greek studies. Although he had never actually studied philosophy, he attempted to replace his philological profession with what he felt was a philosophical calling. But the university’s oversight committee, the Kuratel, did not even consider his candidacy. Instead, in 1871 they appointed Rudolf Eucken, a student of Gustav Teichmüller, who later became widely known as a Nobel laureate in literature. Eucken moved on to Jena in 1874, and his replacement, Max Heinze from Leipzig, left the unofficial second chair after just one year for a position in Königsberg.

Psychologists as holders of philosophical chairs

Since the faculty in Basel considered it important to represent philosophy in its entire breadth with both chairs, and since this breadth was considered to include psychology, a statutory professor with a psychological profile was repeatedly appointed. Among them was Karl Groos, who was primarily active in the field of developmental and child psychology and had made a name for himself as a psychologist in the international academic community with the monograph Die Spiele der Tiere (Animal play) two years before his arrival in Basel in 1896. Groos considered play to be a preparation for the challenges of later life. Even in Basel, he remained true to this research field, which was reflected in the publication of the follow-up work Die Spiele der Menschen (Human play) in 1899, one year after he began to teach. Despite employing natural scientific methods to conduct behavioral research, Groos was also at root a philosopher and linked his psychological approaches to the traditions of German philosophy. Nonetheless, psychology continued to have only a marginal significance within teaching and research in philosophy, and the development into an independent subject progressed slowly and through several intermediate stages throughout the twentieth century.