Auspicious growth: psychology becomes a faculty

On 1 April 2003, the Faculty of Psychology was established as the seventh faculty of the University of Basel. In its first fall semester, the number of new enrollments in the discipline exceeded two hundred for the first time, marking a one-third increase over the previous year. This surge in student enrollment was accompanied by significant expansion. In 2010, the faculty boasted nine divisions, each led by a full-time professor.

The first moves toward the expansion of psychology at Basel date to the threshold of the faculty’s founding. The appointment of Michaela Wänke as professor of social and economic psychology at the beginning of the summer semester of 2002 marked the fourth professorship in the field. Barely a year later, just weeks before the inaugural celebrations of the new faculty, Silvia Schneider was granted a promotional professorship by the Swiss National Science Foundation. These two new professors laid the foundational for the transformation of the discipline into a faculty.

New divisions, new positions, new people

In the subsequent years, the addition of new personnel resources remained one of the most defining characteristics of the growing institution. In the fall of 2003, Silvia Schneider was appointed as assistant professor in the Division of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, a position she held as a full professor beginning in 2006. Also at the beginning of the winter semester of 2003, Ralph Hertwig commenced his role as an assistant professor. Initially tasked with focusing on applied cognitive sciences, Hertwig was appointed in 2005 as a full professor and head of the Division of Cognitive and Decision Sciences.

In the same year, the Division of Developmental and Personality Psychology was established, under the direction of Alexander Grob as a newly appointed full professor. From 1 January 2006, in connection with the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) SESAM, the Division of Epidemiology and Health Psychology was established, headed by Roselind Lieb as an associate professor.

National Centre of Competence in Research SESAM

Concurrently with her associate professorship, Lieb took on the role of managing director of the NCCR SESAM (Swiss Etiological Study of Adjustment and Mental Health). This long-term project, led by Jürgen Margraf, a psychology professor from Basel, was approved by the Swiss National Science Foundation in March 2005 and was funded with 18.4 million Swiss francs for the first four years.

The focus of the study was to observe the psychosocial health of around 3,000 children from the twentieth week of pregnancy until their twentieth year of age. To gain insight into the complex causes of healthy psychological development, psychological, social, and biological-genetic factors were to be considered and collected through behavioral observations, questionnaires, interviews, and biological examinations. Six individual component studies were planned to use subsamples of the main study for additional questions, and eight more substudies were to be conducted based on their own samples.

In March 2008, two years after the program started, the SESAM project management had to announce the termination of the main study because it was not possible to find enough expectant first-time parents in the targeted areas of Basel, Zurich, Bern, and Lausanne. In the summer of the same year, the Lessons Learned working group appointed by the Swiss National Science Foundation identified three additional “trouble spots” that had led to the study’s failure: insufficient clarification of the legal framework, inadequate regulation of the responsibilities and review procedures of the involved ethics committees, and the reactions of the political and media environment.

The evaluation, however, also concluded that the scientific quality of the research project was beyond question. The SNF working group additionally noted: “The NCCR SESAM was reviewed at the application stage and during two site visits at the implementation stage by two independent panels of international experts and rated as excellent in quality. Therefore, this report does not further address the aspect of quality.” What was missing – and this was the working group’s main recommendation, with an eye toward future programs characterized by a larger scope or controversial content – was a thorough “feasibility study.” Not only the scientific viability but also the legal and ethical feasibility should have been examined in advance to identify potential problems before the funding decision.

On 19 January 2009, the Swiss Federal Department of Home Affairs approved the application submitted by the Swiss National Science Foundation at the end of 2008 to discontinue the NCCR SESAM. After a good year of winding down, the research consortium was to be dissolved on 30 September 2010. The eight component studies, which were designed independently of the main study, as well as the preliminary studies conducted for the larger project, were expected to provide publication-ready results by then. The integrated biobehavioral infrastructure established as part of SESAM at Birmannsgasse 8, which enables research work at a high technical and security level, was also to remain in place.

Unconventional approaches to familiar questions

The establishment of the NCCR SESAM and the rapidly added divisions not only expanded but also reoriented the discipline of psychology at Basel in many respects. This is particularly evident in the Division of Molecular Psychology, founded in April 2007, which relies heavily on natural scientific research methods. The close connection with the Faculty of Science is already evident in the fact that the department head, Andreas Papassotiropoulos, also took over the leadership of the Life Sciences Training Facility at the Biozentrum (Center for Molecular Life Sciences). This focus not only represents a new direction within psychology at the University of Basel; it was, in fact, the first chair in the field of molecular psychology in the entire German-speaking area. The primary goals of the new division were defined as exploring the molecular bases of human memory and applying these findings to develop therapies for memory disorders.

Psychology has nevertheless not transformed into a new science; its subject of inquiry has essentially remained the same. The same human being as a subject of experience and action who was at the center of Hans Künzli’s understanding of science continues to be of interest. What has changed is the method of investigation. Alongside the method of phenomenological description and hermeneutic understanding based on observation and dialogue, approaches from cognitive science and neuroscience have been developed. These new methods attempt to explain and trace the processes underlying observable behavior in terms of information processing across various levels, from behavior to the molecule. Areas studied in this way include pattern and color recognition, simple learning and memory achievements, or the planning of sequences of actions.

Even classically psychological issues such as emotion and motivation, mental health and illness, or personality development are tackled in a way that combines theoretical claims with empirical-experimental methods from the field of natural sciences. The term “translational research” was coined to describe this linkage – a research agenda in the life sciences that is deeply embedded in the new faculty, especially in the “molecular bases of mental health and human development.”

The natural sciences have provided psychology with a model not only in their methodologies but also their distinctive spirit of innovation and progress. Projects are deemed promising that venture into previously unexplored territories, bringing fresh perspectives and enhancing the faculty’s profile. According to the faculty’s evaluation in August 2008, the orientation of the new divisions had “eschewed well-trodden paths in favor of exploring new frontiers.” This enthusiastic embrace of novelty likely stems from more than just scientific curiosity. Making a compelling case to the outside world has become increasingly crucial, especially in securing third-party funding. This strategy of championing innovation has proven successful for psychology, as evidenced by the statistics. In its first four years of existence (2003–2006), the Faculty of Psychology saw its third-party funding soar from 100,000 to 4.6 million Swiss francs.

Limits of growth?

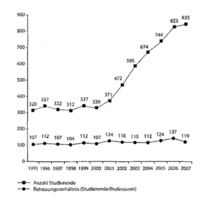

Not only did research funds increase, but the number of students also grew every year. The increase in psychology students surpassed other Swiss universities and even led the trend in neighboring countries. Annual reports from the Faculty of Psychology reveal that the target size of 800 to 850 students set for 2010 was already reached in 2006. Since the number of new students continues to exceed the number of graduates, further growth is expected. This has repeatedly led to bottlenecks in teaching in recent years.

The issue of excessive teaching loads has been a challenge for the faculty from the start and was addressed by Klaus Opwis in his “Address at the Founding of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Basel,” delivered on 26 May 2003: “The large numbers of students in psychology mean significant financial income for the university. Economically speaking, psychology is a success story for the university. We hope this continues, but we also naturally want this success to be more visible where the efforts are being made – in the education of psychology students.”

As of 2010, this wish had not yet been fulfilled. So it is not surprising that the annual reports since 2003 consistently conclude with a note about the challenges of the increasing student enrollments: “The number of students continues to increase; the associated burdens can only be managed with the committed and significant effort of the staff.”

Initially, these burdens were the starting point for acknowledging the staff’s efforts. The report for 2007, however, struck a different and more emphatic tone for the first time: “The successes in research ... were achieved despite a continuous massive overload in teaching. This overload remains the main problem in the area of teaching in 2007. The supervision ratio of 119 students per full-time professorship is still completely unacceptable.”

The abovementioned “Evaluation of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Basel” expresses its dissatisfaction in the final chapter on strengths, weaknesses, and development perspectives in similar terms: “For over a decade now, the number of students per full-time professorship has been over 100. According to CRUS guidelines, the desired supervision ratio is 1:40 (professors:students).” With the resources available in 2010, it was no longer possible to provide central elements of the bachelor’s and master’s programs in sufficient quantity. Moreover, a continuous overload situation also threatens the quality of research and affects the qualification work of the academic staff.

Academic faculty have been partially relieved of administrative tasks after the addition of new administrative positions – notably, the office of the managing director established in October 2006 with the hiring of Jean-Jacques Jobin. With the number of students continuing to rise, a decision between limiting admissions and expanding teaching capacities is unavoidable.