Becoming an independent discipline

During the twentieth century, psychology gained increasing importance within philosophical teaching and research. Still, it was the philosophers who represented psychology – as a philosophical subdiscipline. It was not until the mid-1940s that psychology in Basel acquired true faculty representatives of its own. Another two decades would pass before these extraordinary (associate) professorships became full professorships.

The education system demands a “science of the soul”

The strengthened position of psychology was not a result of internal university considerations. It followed a suggestion from Basel educators, who demanded the establishment of a new statutory chair after the vacancy of the second chair supported by private foundations in 1916. The request was bound up with a revision of the Basel law governing schools, aiming to link the professorship to the task of instructing prospective teachers in the laws of mental life and the educational principles they entailed.

After many consultations and the collection of numerous expert opinions, the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Kuratel were ready to meet the demands being made by the city’s education system – yet only to the extent that the aims of science were granted uncontested priority. The university did not want to commit itself too rigidly to the practical concerns of local education.

This could only benefit the development of psychology in Basel, as it meant prioritizing psychology over educational theory. This hierarchy was also reflected in the subject area to which the professorship was to be devoted. In its “Draft for a Council Recommendation concerning the Establishment of a Second Chair of Philosophy at the University,” the Department of Education suggested to the Basel Governing Council a professorship for “philosophy with special consideration of psychology and pedagogy.”

However, the Grand Council decided on a chair for “pedagogy and general philosophical disciplines,” which initially threatened to disadvantage psychology once again. The amendment to the University Act which came into effect on 22 August 1917 provided for the immediate establishment of the chair. This did not, however, result in an immediate appointment. After prolonged disputes between the responsible institutions in the university and the city government, Otto Braun, formerly a professor in Münster, took up the position as the first full professor in 1920.

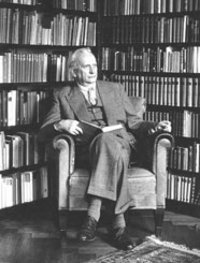

Everything is ultimately psychological – the philosophers Häberlin und Jaspers

When Braun died unexpectedly after two years in office, Paul Häberlin from Bern brought a phase of continuity to the second chair of philosophy. This also set in motion a gradual consolidation for the psychological approaches at the university, as the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences had appointed Häberlin specifically for his psychological expertise. In a recommendation dated 6 May 1922, the dean wrote to the Basel Board of Education about Häberlin’s profile: “Trained in both the humanities and the natural sciences, he will complement the teaching of philosophy at our university as a specialist psychologist, not only in line with the criteria we have set out but also, and especially, in way that will be productive as measured by modern pedagogical methods. In a series of widely received texts which reflect the constant development of his thought, he has laid out the principles of empirical psychology, furnished practical pedagogy with philosophical foundations, and elevated philosophy to a true education of the spirit.”

Häberlin’s seriousness about the psychological emphasis was evident from his inaugural lecture in Basel on 13 November 1922, titled Der Beruf der Psychologie (The vocation of psychology), addressing the field with which he was most directly engaged at the time. The lecture was published in print the following year and was part of a rapidly produced series of psychological publications. In the same year, 1923, Häberlin published Der Leib und die Seele (The body and the soul), a work he had completed while a professor in Bern. One year after that, his elementary treatment of psychology Der Geist und die Triebe (The spirit and the drives) appeared, followed in 1925 by the Der Charakter (Character). Continuing to develop psychology in teaching and research remained Häberlin’s concern until his retirement in 1944 and beyond. He highlighted the importance of psychology for a fundamental understanding of human beings, especially in those writings where psychology might initially have been assigned a subordinate role. In the 1948 essay “Die Eigenart der biologischen Wissenschaft” (The uniqueness of biological science), Häberlin emphasized that for human beings, “biology” in its full sense could only be a psychological biology, understood as “the psychology of the foreign policy of the soul.” Likewise in the year in which he retired, Häberlin wrote an unpublished manuscript on “Wesen und Aufgabe der Psychologie” (The essence and task of psychology), in which he dealt with the possibilities and limits of psychology, its position within the sciences, and the relationship between body and soul.

In searching for a suitable successor for the now seventy-year-old philosopher and psychologist Häberlin, the university and Basel government soon decided to appoint Karl Jaspers, already sixty-five at the time. In the correspondence between the city’s Department of Education and the Heidelberg philosopher and psychiatrist, Basel showed flexibility regarding salary and pension. However, when it came to the academic orientation of chair, the specifications were not up for negotiation: psychology was to be a focus in addition to the general philosophical disciplines. The agreed-upon title was thus for a “professorship with teaching responsibilities for philosophy, including psychology and sociology.”

Jaspers seemed particularly suited to such a teaching task because he found his way to philosophy through psychology. Originally a trained physician with a doctorate, he completed his habilitation in Heidelberg in 1913 in the field of psychology with his textbook Allgmeine Psychopathologie (General psychopathology) and was promoted to extraordinary (associate) professor three years later. A psychological approach remained decisive in his work, which was essentially philosophical; one text that remained a guiding light for entire intellectual career was his Psychologie der Weltanschauungen (Psychology of ideologies), which he published in 1919 as a professor of psychology. Even in 1950, two years into his tenure as a professor of philosophy in Basel, Jaspers emphasized in an unsent letter to Martin Heidegger the importance of the approach pursued in this work: ”As I understand my work, it is still fundamentally about the same thing that manifest itself for the first time in Psychology of Ideologies without my having any practice in the craft of the philosopher.”

Jaspers was guided by a claim from Aristotle with which Häberlin would probably have agreed: “In a sense, the soul is everything.” For Jaspers, there was hardly anything in the world of humans that did not have a psychological aspect in this broader understanding.

Nonetheless, it was philosophy in a strict sense that always dominated the approaches taken by these philosophical chairs. Even for the most psychologically inclined representatives of philosophy in Basel, Häberlin and Jaspers, psychology was primarily seen as an indispensable tool. Philosophers were to use it to serve philosophy – not to make psychology the preeminent science.