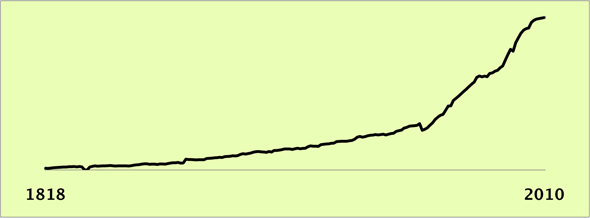

Development of the teaching staff in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: numbers, contexts, and comparison

Data on the teaching staff have been available since 1818. This reconstruction situates the numerical growth of these university members within the institution’s political, social, and scientific-historical contexts. Comparing Basel’s situation with that of other universities, it furthermore offers insight into more general historical trends of these institutions.

The numerical data and the changes in context suggest that the development of the teaching staff at the University of Basel can be divided into three phases. For the period between the university reforms of 1818 and 1866, notable developments are a restructuring and an expansion. Both were influenced by the unique local historical situation in Basel: the political rivalry between conservative and modernizing forces, which gained new momentum with the separation of Basel-City and Basel-Countryside in 1833 and culminated in 1851 with the demand made by liberal members of the Grand Council to abolish the university as an “elite institution.”

In the context of the second Industrial Revolution, a new stage of development began at many European universities around 1870. Until the 1960s, Basel’s teaching staff experienced a rather steady expansion overall. However, clear phase shifts are evident at the level of university faculties and subjects. Medicine, in particular, saw a remarkable rise after the university reform of 1866. By contrast, the expansion of planned professorships in the humanities lagged compared to German universities.

In the 1960s, the existing pattern shifted. Under the influence of an economic boom and the systemic competition of the Cold War, Western universities enjoyed an unprecedented surge of support. In Switzerland, the acceleration of this expansion was more modest than in neighboring countries. Basel’s expansion moreover trailed that of other Swiss universities until the 1980s. Data collected consistently, and not just for selected years, clearly show that the initially parallel expansion of all status groups diverged after the economic downturn in 1973. Professors stagnated, while extraordinary (associate) professors and mid-level faculty continued to expand.

Linear, exponential, and hyperbolic growth

Drawing from the work of Matthias Kölbel, who calculated the growth of resources devoted to academic knowledge production in Germany from 1650 to 2000, we can generally classify Basel’s development. Kölbel concludes that the growth of such resources – specifically, the number of universities and professors – was nearly hyperbolic: the growth rate continuously increased, and the doubling time shortened. This was possible because the conditions for academic knowledge production were continuously improved with the development of the knowledge society characteristic of the modern world. Kölbel’s study provides meticulously calculated evidence for his overall thesis that modern society has been increasingly permeated by science and forms of academic knowledge.

Over the long term, such rapid growth remains unrealistic. After 1970, the development of such resources fell out of proportion with the fundamental variables of population and economic output, which increased at a more measured pace. Kölbel sees this as the structurally induced “end of resource growth.”

The development of personnel at the University of Basel in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries proceeded at a somewhat slower pace than the overall trend in Germany. The number of ordinary and extraordinary (associate) professors did not in fact increase exponentially: the growth rate was not entirely constant, and the doubling period slightly increased. Between 1840 and 1879, the number doubled in thirty-nine years, between 1879 and 1922 in forty-three years, and by 1966 in forty-four years.

Since the statistics on Basel’s teaching staff available to us, unlike Kölbel’s calculations, also include subprofessorial status groups, we can refine his assessment of the period after 1970. Including all personnel categories, these years in Basel show a transition to (steep) linear growth. In terms of financial resources expended, this trend is less meaningful because expensive and inexpensive categories are mixed – and were consciously mixed by education policymakers in the 1960s. However, these data remain significant regarding the staff available for teaching duties and research capacity.