The deposition – an initiation ritual

To become a student in Basel with academic citizenship, one had to go through a classical initiation ritual known as the deposition, along with matriculation.

This custom, prevalent at Central European universities, especially in the region of the old empire since the late Middle Ages, aimed to firmly instill the norms of the corporation in future students. Initially a mere fee for the bursaries called the “beanium,” it developed into a complex symbolic process in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The “depositio cornuum”

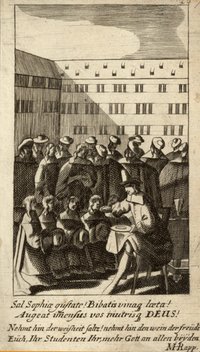

The core of this ritual involved cutting off previously attached artificial horns, the “depositio cornuum,” which give the ritual its name and are still proverbially known in German as “shedding one’s horns” – equivalent to “sowing one’s wild oats.” In Basel, the procedure was likely carried out in the courtyard of the Upper College in the presence of the dean and other members of the Faculty of Philosophy, along with the bedell and the “depositor,” who was appointed by the senior student of the Alumneum. During the ritual, the prospective students had to wear specific garments, such as ox hides and various symbolic accessories, including the requisite horns and oversized teeth.

These items were then roughly removed by the depositor, sometimes involving physical force, using oversized wooden saws, axes, planes, and drills. This ritual undressing was accompanied by a speech from the dean, explaining the meaning of the ritual and its symbols to the candidates. The students were admonished to obedience, diligence, and a life of virtue. The cutting-off of the horns was interpreted as symbolically shedding bad habits and poor conduct.

Only afterward did the dean proceed with the registration in the matriculation book of the Faculty of Philosophy and the swearing-in. The entire process cost the students one pound, with fees increasing for a private deposition excluding spectators. Resistance to the ritual arose early on, mainly due to the costs, but it wasn’t until the early eighteenth century that universities across the old empire began to abolish the practice and revert to just the fee.

In Basel, the deposition was not completely abolished until 1798. The reasons for its persistence were primarily economic, as the Faculty of Philosophy would then lose the associated fees.

The social significance of the deposition, considered the most spectacular academic ritual, was multifaceted. First, it marked social distinction, separating those subjected to it from those who were not, while also enabling social gradations based on the fee paid. For the faculty and its members, the deposition provided a crucial source of income within the university’s socioeconomic system. Additionally, for the entire corporation, the ritual acted as an integrative initiation, helping to incorporate future members. Given the significant privileges it afforded, including in legal matters, the ritual was a key mechanism for instilling academic norms in the students.