Honorary doctorates at the University of Basel since 1823

On 7 February 1823 the University of Basel awarded its first honorary doctorate to Rudolf Hanhart, the rector of Basel’s Gymnasium and an extraordinary (associate) professor of pedagogy, recognizing his contributions to local education. In doing so, the Faculty of Philosophy embraced a reform that had emerged from new developments implemented across Europe beginning in the early nineteenth century. Eventually, these changes became emblematic for academic recognition in the modern period. By 2015, the University of Basel’s faculties had awarded over 750 honorary doctorates.

The honorary degree in 1823 marked the Faculty of Philosophy’s first use of its new regulations, enacted that same year, empowering it to recognize significant research and contributions to science in teaching and research by awarding a doctorate free of charge. At roughly the same time, similar wording appeared in the doctoral regulations of the Faculty of Theology. The University of Berlin, founded in 1810 at the initiative of Wilhelm von Humboldt, had been the first to formally integrate the concept of an honorary doctorate into faculty guidelines. These regulations defined such a degree as an unsolicited distinction awarded by the faculty to recognize scientific merit; unlike a standard doctorate, it was also awarded without any fees being assessed. This model likely came to Basel with the theologian Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (1780–1849), who was a founding professor at the University of Berlin before being appointed to Basel in 1822. Not long before this innovation, Basel’s University Act of 1818 had brought the university under state control, necessitating a complete overhaul of academic programs. These reforms established the doctorate as the central qualification in academia, prompting a need for new regulations.

Honorary doctorates as a new form of doctoral degree

The Faculties of Theology and Philosophy made it clear from the outset that they could confer doctorates both regularly (rite) and honoris causa, making honorary doctorates the norm during the early decades of the nineteenth century in theology and in the humanities and natural sciences. In the Faculty of Theology, academic qualifications had previously been less important than church ordination, and the Faculty of Philosophy had not been regarded as a full-fledged faculty nor included in the regular awarding of doctorates before the 1818 reforms. Both faculties seized upon this new option, awarding titles to their own professors and to colleagues from other Swiss academies, such as in Bern or Zurich, which were not yet universities. By the 1833 upheavals that led to the division of Basel-City and Basel-Countryside, the two faculties had already awarded thirteen honorary doctorates, a substantial number given the small student body. Following the university’s reestablishment after the 1835 cantonal division, all faculties collectively awarded nine honorary doctorates to visiting scholars, publicly announced at the opening ceremony. This was the university’s first strategic use of the honorary doctorate to clearly communicate its continued authority and ability to award academic degrees.

Celebrations and anniversaries as catalysts

The 1835 celebrations served as an important precedent and launch of a new tradition: from then on, festivals and anniversaries became prime opportunities to award honorary doctorates. By 1910, the university’s faculties awarded half of all honorary doctorates at formal events, with its anniversaries in 1860 and 1910 taking center stage. Other notable events included the fiftieth anniversary of the Voluntary Academic Society, which coincided with the university’s 425th celebration in 1885, and the city’s 1901 celebration of Basel’s 500th year of membership in the Swiss Confederation, staged as a grand historical spectacle that also yielded numerous honorary doctorates. Similarly popular occasions included commemorations of scholars on the anniversaries of their birth or death, as well as inaugurations of new university buildings such as the Bernoullianum and the museum on Augustinergasse – both of which inspired the university’s faculties to award additional honorary doctorates. These celebratory doctorates peaked in the twentieth century, when the university’s 500th anniversary included a special ceremony awarding twenty-nine honorary doctorates – all to men.

The evolution of the honorary doctorate

In the early years, the Faculties of Theology and Philosophy, covering the humanities and natural sciences, awarded the majority of honorary doctorates. This was in part because, for these faculties, the doctorate still embodied broad knowledge and learning in the Humboldtian tradition, rather than the professional credential it had become for medicine and law. Over time, this led to a gradual expansion of the grounds for honorary doctorates, which increasingly were granted in recognition of contributions to society, with the habilitation later added to the doctoral degree. This development caused the honorary doctorate to increasingly diverge from the traditional (rite) doctorate, eventually allowing for a Doctor honoris causa to be granted independently of any existing doctorate in the field – a concept that would have been unthinkable when these reforms were first introduced.

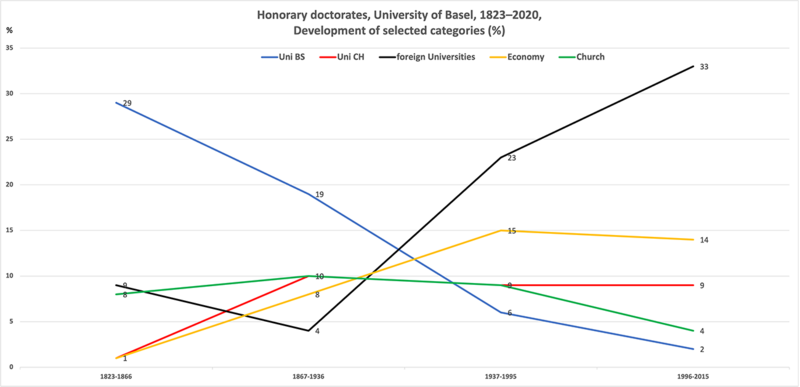

Throughout the twentieth century, honorary doctorates for professors from international universities increased steadily, eventually making up about one-third of all honorary awards; this trend reflected the increasing internationalization of what had previously been a regionally focused institution. During this time, honorary doctorates for business leaders also became much more significant, while awards to individuals from the church or from within the University of Basel – once predominant – became rare. Likewise, honorary doctorates for academics from other Swiss universities were increasingly replaced by international recognitions.

Differences and growth among the faculties

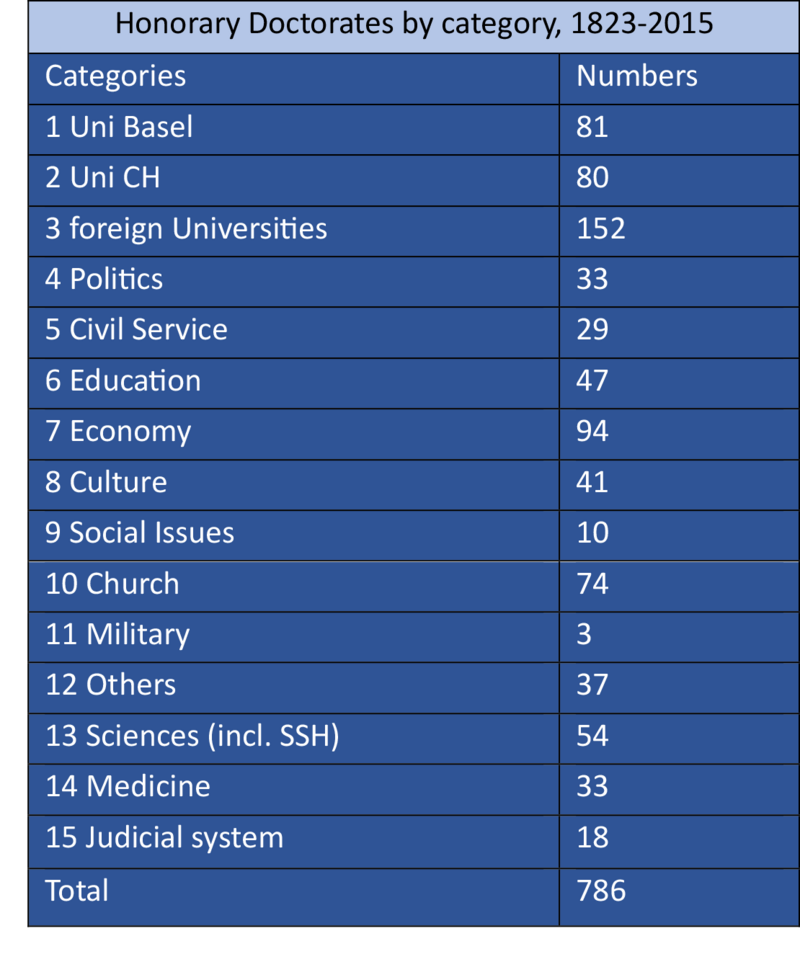

In the nearly one hundred years after the introduction of the honorary doctorate (i.e.., up to the 1910 anniversary), the faculties awarded a total of 180 such degrees. The Faculties of Theology and Philosophy together awarded roughly 80 percent, with 146 honorary doctorates. By the university’s 1960 anniversary, this number had grown to 390, doubling again by 2015. One factor in this growth was the division of the Faculty of Philosophy into separate faculties for the humanities and natural sciences in 1937, with each independently awarding honorary doctorates. The establishment of a Faculty of Economics in 1997 and a Faculty of Psychology in 2003, both formed from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, further increased the annual number of honorary doctorates awarded.

Together, the original two philosophical faculties (the Faculty of Philosophy and History, and Faculty of Philosophy and Natural Science) awarded nearly half of all honorary doctorates between 1823 and 2015, conferring a total of 350 degrees, with 101 degrees coming from the newly established Faculty of Philosophy and Natural Science after 1937. This total also includes 31 honorary economics doctorates awarded since 1922. The Faculty of Theology ranks next with 166 honorary doctorates (including nine licentiates), most of which were awarded in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Faculty of Medicine awarded 143 honorary doctorates, and the Faculty of Law 92. The recently established Faculties of Economics and Psychology have not yet significantly impacted these numbers.

Delayed recognition for women

It took 113 years for the University of Basel to award an honorary doctorate to a woman: in 1936, Helen Mary Allen received the degree “for editing the letters of Erasmus, which she and her late husband worked on over thirty-five years.” Typical for the time, her achievement was recognized only in connection with her husband’s work. In the following years, the faculties continued to be slow in honoring women, awarding honorary doctorates mainly for impressive social or civic contributions rather than for specific academic accomplishments. By the late 1970s, only thirteen women had received honorary doctorates (one in theology, one in law, five in medicine, two in natural sciences, and four in the humanities). Between the time women were admitted to study and 2010, 695 men and only 49 women (6.5 percent of the total) had received honorary doctorates. During the anniversary year, six men received honorary doctorates, but only one woman. In 2021, in a deliberate change, all honorary doctorates were awarded to women, though men continue to receive most these recognitions.

Integration into the Dies academicus in the twentieth century

Originally, honorary doctorates were awarded at any time, apart from special events. When a nomination was approved by the faculty, a Latin diploma with a laudation was prepared and sent to the recipient, usually without ceremony. Honorary doctorates were, however, publicly announced at events such as the university’s opening celebration in 1835 and the combined celebration in 1885 at Martinskirche. In the twentieth century, it became customary to read honorary doctorates aloud at the Dies academicus, an annual academic celebration originating in the early nineteenth century. The rector’s 1953 annual report notes that, for the first time, all honorary doctorates – men all – received their diplomas in person at the church, establishing a tradition that continues today. Today, honorary doctorates are well established as part of the annual celebration, and awards outside this formal occasion are now rare.