The existential crisis of 1833

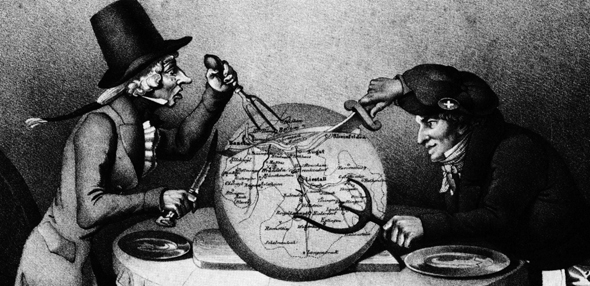

The civil war between the conservative city and the liberal-radical rural canton in the years 1830–1833 had a profound impact on the university. The sociopolitical conflict exposed the university to internal tensions, while its outcome – the division of the canton and of state assets – posed financial difficulties to the city and thus to the university.

The conservative city-state of Basel could not completely avoid the reformist spirit that briefly surged across Europe around 1830. Basel faced demands from the rural population that the cantonal parliament and a possible constitutional council should be composed proportionally to the various parts of the population. This would have meant a majority of the countryside over the city and a dominance of radicals over conservatives. The high affairs of state (such as security policy and tax policy), as well as the shaping of trade and commerce and cultural policy (including the school system and the university!) would have fallen into the hands of “peasants.”

For the leading faction of professors, the uprising of the rural population not only showed an insubordinate lack of respect but represented a campaign against higher education driven by ignorance.

The forces demanding political and economic equality for the countryside, by contrast, came mainly from an urban bourgeois milieu, even including some university graduates, such as the lawyer Stephan Gutzwiller, the leader of the Countryside Party, who came from the Catholic town of Therwil. The many pastors who demanded obedience to the city authorities from the pulpits of rural churches were for the most part also educated predominantly in the city.

A divided university

Conservative professors supported the city’s position as a matter of course: the theologian Carl Rudolf Hagenbach-Geigy, for instance, who became rector at the age of 30 in 1831, stood guard in the same year with a gun to protect the city and participated in patrols for its protection. Andreas Heusler-Ryhner was apparently able to effortlessly combine his position as a professor for federal and cantonal constitutional law with his role as head of the conservative Basler Zeitung, founded in January 1831, and, since October 1831, his membership in the Lesser Council. He was a committed defender of “historical law” (against ahistorical natural law) and was known for his aversion to what he called “liberal demagogy.” Heusler described the canton of Appenzell-Ausserrhoden as an “honorable outlaw state” because it protected the freedom of the press and those making radical arguments against conservative Basel. He was supported in these efforts, and in his work at the Basler Zeitung, by Christoph Bernoulli and Christoph Friedrich Schönbein. Schönbein, a Swabian appointed to a position in Basel in 1828, was granted honorary citizenship in 1840 because of having “demonstrated his loyalty to our city in word and deed during our times of turmoil.”

Feeling challenged by the conflicts of the moment, professors who had advocated for progressive ideas in their courses now sided with the conservative city against the legitimate expectations of the countryside. While still calling themselves liberal, they rejected radical liberal positions and their excesses, so-called vulgar radicalism

This was particularly the case with Alexandre Vinet, who began teaching in Romance philology at the age of 20 in 1817 (since 1819, as an associate professor) and had lectured on the sacred right of rebellion against divine authority, but now interpreted the conflict in terms of protecting urban law against rural power.

It is noteworthy that German emigrants such as de Wette, Jung Röper, Meissner, and Gerlach were also involved in this local conflict and fought on the side of the city in the academic Freicorps. The “foreigner” Wilhelm Martin de Wette condemned Swiss colleagues who championed the cause of the countryside. Carl Gustav Jung wrote an antiradical drama Der Revoluzzer under a pseudonym and accompanied the urban campaign against the rural forces as a troop doctor in August 1833. After the debacle at Hülftenschanz, he had to escape across the Rhine by boat for safety.

As early as 1831, sixty students had formed an armed corps to defend the city against the rebellious countryside, perhaps reflecting the position held by a majority of students.

There was nevertheless also a faction at the university that sympathized with the rural population, most prominently Ignaz Paul Vital Troxler from Beromünster in Lucerne, who had only been appointed full professor of theoretical and practical philosophy and education in 1830 and became rector of the university the following year (against the candidacies of Christoph Bernoulli and Karl Rudolf Hagenbach). The “fifty-year-old firebrand” Troxler sympathized with the revolutionaries in the countryside, prompting a police search of his home. Nothing was found, however, as the Vir Magnificus – a relentlessly biting critic of conservative forces in Basel whose published opinions in the Appenzeller Zeitung were well known – had burned his correspondence of the previous nine months. This must have included a large number of letters, as he was reputed to have received four to five of them every day.

De Wette concluded that his support for Troxler’s appointment to Basel had been a grave mistake, saying Troxler had been driven by the devil and calling Troxler a creature from hell. In September 1831, Troxler was removed from office. Basel authorities accused him of neglecting his duties as rector and his teaching obligations, and of having secretly left the city. During the time he was subjected to police interrogations, Troxler did not teach, partly due to time constraints and partly in protest. After an interlude in Aarau, he moved to Bern, where he was appointed in 1834 to the chair of philosophy at the newly founded university. Wilhelm Snell, who had been rector in 1830, joined him in leaving Basel for Bern. Snell had vehemently supported Basel-Countryside, served as legal advisor to the young canton of farmers, and was named an honorary citizen in 1833 for his services. Snell, dismissed from the University of Bern in 1845 because of his political agitation, returned to Basel-Countryside, where he served as a district councillor from 1845 to 1848 and lectured in Liestal.

An acute crisis with long-term effects strengthening the university

After the division of the canton into the half-cantons of Basel-City and Basel-Countryside, a fierce dispute erupted over whether the university property should be included in the division of state assets decreed to accompany the cantonal separation, or whether the assets should be classified as property belonging to the university foundation unaffected by the separation. The arbitration panel decided, by vote of its chair from Zurich, against the city. Councillor and law professor Andreas Heusler descried this as “extortion under the guise of justice,” and in 1929, Rector Erwin Ruck, professor of public law, referred to this decision in his rectoral address as a “miscarriage of justice as demanded by the principles of civil law.” Edgar Bonjour concluded later, in 1960, that the decision had neglected “higher cultural aspects.” With some effort, it was at least possible to avoid a literal division of the assets, since the university property could not actually be sold and thus had no real market value, with a settlement agreed for payment of one-half of the value following a deduction of 25 percent.

Theoretically, the canton of Basel-Countryside could have demanded a buy-out sum of 331,451 Swiss francs for 60 percent of the university’s assets. In 1836, a new law stipulated that the university’s assets could not be sold. The previously fragmented system of accounting was consolidated, and university collections were placed under the authority of newly established museum commissions. The young canton of Basel-Countryside used part of the payout from the city to establish new elementary schools.

A crisis as an opportunity

The university’s operating costs were reduced by 13.7 percent from around 40,200 to 34,700 Swiss francs (in 2000 this would have corresponded to amounts of 4.0 and 3.5 million Swiss francs). The city used the crisis as an opportunity, that is to say, as a chance to modernize the university. It strengthened the emerging natural sciences while also hoping to produce benefits for the “advancing industrial sector.” In 1834, all professorships were temporarily declared provisional, and even though the professor salaries set in 1835 were kept low, they still amounted to 160,000 Swiss francs in contemporary value (2000). Additionally, performance bonuses were promised. More flexibility was introduced in the composition of the faculty through the introduction of extraordinary lecturers, allowing the government to address “emerging needs.” This was considered a new beginning, and on 1 October 1835, “the restoration of the university” was celebrated with a ceremony in the cathedral.

Yet the division of the canton and its restrictions also spurred long-term effects strengthening the university: many were convinced that Basel – especially now, more than ever – needed to compensate for what it had lost in terms of territory and assets with “intellectual and spiritual activity.” One result was the Voluntary Academic Society (Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft, FAG), which provided significant amounts of ongoing support to the university for extraordinary projects. Another outcome of this crisis: in 1836, an academic guild was created alongside the city’s other fifteen guilds.