The University Act of 1937

A new University Act was passed in 1937 – expressing spirit of new beginnings, along with a desire for institutional structures that would be appropriate to the historical circumstances and for improved material infrastructure. This new beginning is quantifiably reflected in the number of legally apportioned professorships increasing from twenty-four (in 1866) to forty-one and then to fifty-one (in 1937), while the process for creating additional professorships was simplified.

The Act, which would provide a solid foundation for the next half-century, was preceded by a decades-long history: after 1900, two decades in which a number of ad-hoc policy decisions were made were followed by an intensified reform process starting in 1926/27, eventually leading to the new law. But why was such a law necessary at all, and what were the most important changes?

One consistent motivation was the fact that the many, less systematic legal changes that had been introduced since 1866 (such as the new, and separate, University Property Act) needed to be consolidated within a new legal and institutional framework. Other reasons included the significant increase in the number of legally apportioned professorships and changes to the salary and pension conditions of university teachers “because of competition from other universities.” Lastly, there was a desire to clarify the relationship between the university and the state and to more extensively regulate the areas of responsibility of the various authorities.

Driving forces

Who were the main proponents pushing for this reform? According to the government’s statement of March 1935, this reform was driven primarily by the government, and more specifically, by Basel’s Department of Education. The proposal points to earlier report that had been addressed to the city’s Oversight Committee for the university (the Kuratel) in January 1918 and reiterates that the committee had been repeatedly reminded of the urgency of the matter in November 1926. In February 1929, the committee also came under pressure from the university. Speaking as rector, Erwin Ruck, an expert in public law, had declared that there could be no justification for any “further delay” and that he could not take responsibility for the “ongoing” (and thus compounding) damage to the university being caused by the situation. In June 1929, the Oversight Committee commissioned Erwin Ruck to draft a University Act. The following year, in his rectoral address, Ruck systematically thematized the university’s legal situation.

In February 1931, the Senate was able to articulate a position as part of the consultation process, leaving the Board of Education to weigh in, which formally took up the reform for the first time in November 1931. Several more years passed before the matter reached Basel’s Governing Council in 1934/35. In March, it was discussed in the Grand Council, followed by a committee consultation, a first reading on 12 November 1936, and then approval “by a large majority without opposition” in the final deliberation of 14 January 1937. After the waiting period to allow for a possible referendum had expired, the new University Act came into force on 2 March 1937.

Preserving the university’s character

The final vote was merely a formality, not even registered by the media. The main negotiations had already taken place in 1934/35. A second reading was required because it was still necessary for the committee appointed by the Grand Council and chaired by Albert Oeri, a member of the Liberal Democratic Party (and editor-in-chief of the Basler Nachrichten) to take a position on three points: 1) the possibility of limiting appointments to a maximum of six years (discussed below); 2) the “anchoring” of the academic character of the Faculty of Theology; and 3) the residence requirement for professors. A rich protocol in the Basel State Archive documents the earlier committee deliberations, showing that on 22 October 1935 discussion topics included whether and how the city could ensure that the Swiss character of what it called its own – “our” – university would be preserved. Ernst Thalmann – a Free Democratic member of the Grand Council, head of the city’s Oversight Committee for the university, and member of the Council of States for the canton of Basel-City – declared that even if protecting the university was doubtless necessary, “perhaps even more so now than before,” this aim did not require a paragraph in the new law. Fritz Hauser, a Social Democrat and member of the Governing Council, fully agreed with him.

The main issue posed by the principles at stake arose in more specifically articulating the university’s autonomy. Ruck emphasized that the university, despite being subordinate to the state, stood on the “ground of self-administration” in crucial areas including outward representation, the election of university bodies, the administration of university assets, its legally guaranteed participation in faculty appointments, the acceptance of junior faculty through second dissertations (habilitations), the regulation of the curriculum, and the setting of tuition fees (i.e., college fees). The question was also discussed of whether the university had the right to issue regulations without the agreement – or even in defiance – of Basel authorities. The solution ultimately entailed including a compromise in the law regulating such details.

Too much dependence on the state?

The proponents of greater autonomy, especially to be found in the liberal milieu of Basel’s traditional families, did not shy away from comparing the close ties between the university and the city with the kind of forced coordination with government policies that was being implemented at the time by the Nazis in the German Reich. Yet as can be seen in the regulations giving the government power to appoint professors, the approach of subordinating the university to state authority prevailed. However, as for the specific details concerning university operations, the new law offered a first-ever, explicit affirmation of academic freedom in teaching and research, combined with an emphasis on maintaining distance from government authority – thus clearly staking out a position opposed to the totalitarian understanding of state and society that had prevailed both to the north and the south of Switzerland. Two years later, academic freedom would reemerge as a theme at the inauguration of the new Kollegienhaus. This freedom included a stipulation in the University Act that religious and political convictions were to play no role in the appointment of professors.

Content of the Universities Act

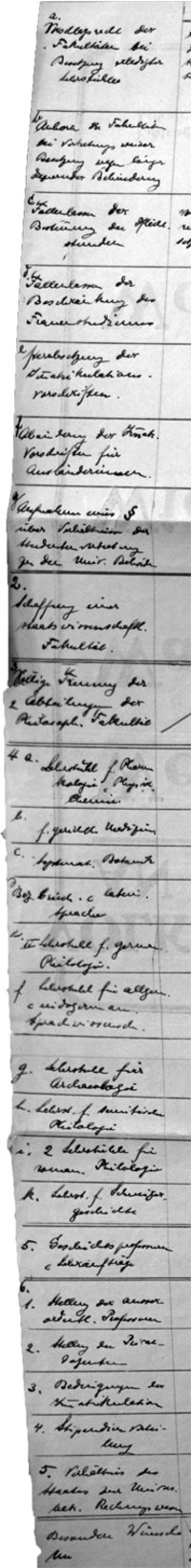

The Universities Act was divided into six sections.

Section 1, building on the previous law of 1866, named the three purposes of the university: “the cultivation of science, training for scholarly and academic professions, and the promotion of intellectual and spiritual life.”

Section 2 defined the powers of the bodies governing the university. The Governing Council was responsible for overall supervision. The Board of Education possessed wide-ranging authority: it was here that all university matters ultimately decided by the Governing Council were first discussed, and that some decisions were taken that are today considered internal university matters (such as budget allocation for the various departments and disciplines). The Oversight Committee (Kuratel) exercised “direct supervision” over the university. Significantly, the Council of Full Professors (the Senate) was not listed in the section on “University Management” but in the following section, “University Faculty.”

Section 3 defined the categories of faculty, distinguishing between full and associate professors, private lecturers (habilitated scholars with the permission and obligation to teach, though lacking paid appointments), instructors, and teaching assistants. The teaching obligation for professors, previously set at ten to twelve hours a week, was reduced to no less than eight. Limiting appointments to six years – a demand that had been expressed in the Basel city parliament – was rejected as it would have meant creating a tier of faculty with lesser rights compared to those already appointed for life. The motive here – revealed by references to a possible “national interest” – was to have means to deal with professors who sympathized with the Nazi regime (see the Gerlach case).

Section 4 regulated the division of faculties. This reaffirmed the division of the Faculty of Philosophy into faculties we might recognize today as humanities and natural sciences, a Faculty of Philosophy and History (Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät) and a Faculty of Philosophy and Natural Science (Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät), formally consolidating a distinction that had already been made on a subordinate level. The regret over this “rift” and the “loss of historical unity” was greater among representatives of the old sciences than among those from the new sciences.

Abolition of the Faculty of Theology?

One controversy that arose, especially outside the university, was whether the Faculty of Theology should be maintained. A motion submitted by Communist members of the Grand Council for abolition was rejected by a vote of seventy to forty-four. The Catholics were generally against secularization and therefore supported the continuation of the Reformed faculty. The Friends of the University (see Supporters and sponsoring associations) also became involved in this discussion, inviting Ernst Staehelin to give a lecture on “The Nature and Task of the Theological Faculty” which they subsequently published in their own series in 1934. One issue this lecture addressed was whether and to what extent donors who endowed university chairs should have a say in appointing their holders. While the theologians wanted to grant these supporters at least the right to propose candidates, the Grand Council remained firmly opposed. Preventing private circles from exercising influence via donations on the intellectual orientation of professors was considered more important than the money this would have saved the state.

For the other two faculties, the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Medicine, no fundamental changes were enacted. The Faculty of Medicine was expanded to include the Institute of Dentistry, and the idea of integrating faculty members in the field of economics into the Faculty of Law, which had been circulating since the beginning of the twentieth century, was rejected. The allocation of new professorships resulted in a certain shift and the following distribution:

- Faculty of Theology, five chairs

- Faculty of Law, five chairs

- Faculty of Medicine, thirteen chairs (an increase of nine)

- Faculty of Faculty of Philosophy and History (today known as the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science), fifteen chairs (an increase of three)

- Faculty of Philosophy and Natural Science (today known as the Faculty of Science), thirteen chairs (an increase of one)

The university’s management structure was strengthened by the fact that the rector, a position held only for one year, was to be supported by a Senate committee to ensure continuity.

Section 5 dealt with the students, divided into two categories (enrolled students/auditing students), and in particular set forth admission regulations. The law, however, did not codify any status for the officially recognized student body.

Section 6 named the regular administrative staff assigned to the rector, consisting of four positions: the secretary, the quaestor, the bedell, and the university sports instructor (created earlier, in 1922).

Impressive momentum

The momentum expressed in this legislative reform is impressive and perhaps a bit surprising, or at least in need of explanation. Did the desire to create a new University Act stem from the same desire that led to larger construction projects such as the Art Museum and later the Kollegienhaus, or the significant social project of Basel’s “work penny” initiative (the job creation program introduced in 1936, financed by a one-percent tax)? Josef Zwicker (1991), for one, saw in the University Act a parallel to the later Kollegienhaus. Was the reform a product of a general desire for modernization, as can be observed in other areas, or was it (also) part of broader efforts at crisis management? What roles were played by Basel’s director of education Fritz Hauser and Erwin Ruck, a figure who was highly engaged in a number of ways, as a professor of public law, rector in 1930, and promoter of the Friends of the University association taking shape at the time? And was the interwar period in Europe a kind of founding era for universities, making the events in Basel merely a variant of a transnational phenomenon? The richly illustrated book on universities published at the time by Erwin Ruck in a series at Lindner Verlag does offer some indications this was the case.