The dispute over privileges: the seventeenth century

While the second half of the sixteenth century was characterized by a certain international influence and intellectual openness, the focus shifted in the seventeenth century. A move toward stronger regionalization or even family-based ties coincided with increased tensions between the university and the absolutist authority of the city.

The seventeenth century was this marked by developments that were strangely out of sync or even running in opposite directions. Members of the city’s elite families of burghers played an increasingly important role in the university. Meanwhile, city authorities, who belonged to the same burgher families as the university’s professors, steadily increased the pressure to finally incorporate the university (and thus many of their – often close – relatives) into the absolutist-authoritarian state. Demands were made to abolish the university’s special rights and privileges, and to not only integrate its faculty and the exceptional status it enjoyed into the city’s social structures but also to subordinate them in the protocols governing social hierarchy.

The “family university” and the urban elite

Of the seventy-five professors who taught in Basel between 1529 and 1600, three quarters came from southern Germany and Alsace, from other regions of Switzerland, and from France, Italy, and Holland; only a quarter were Basel residents. In contrast, veritable scholarly dynasties developed in the seventeenth century. Of the eighty professors who taught in Basel between 1600 and 1700, about 60 percent belonged to a circle of fifteen Basel families, including the Burckhardts, Faesches, Buxtorfs, Bauhins, Becks, Platters, Wettsteins, Wollebs, and Zwingers. This development continued into the eighteenth century, albeit in a diminished form. Many professors were also bound by family ties.

Often, as the names suggest, the professors came from the same families that also held the most important city offices. From the Reformation until 1737, the head of the Basel church, the antistes, was always a professor of theology, and the entire clergy was subject to the theological faculty, which until the end of the seventeenth century included the pastors of the four main churches (Basel Cathedral, St. Peter's, St. Leonhard's, and St. Theodor's), in addition to the university’s two professors of theology.

The familial, social, and political relations between the university and the city’s elite must therefore be described as exceptionally close since at least the seventeenth century, and on a political level, the contrast between the city and the university was primarily institutional and legal, rather than being constituted by different social backgrounds, separate worlds, or completely incompatible cultural codes.

In contrast, the increasing pressure to socially and legally conform exerted on all social groups by the city’s absolutist authorities seems to have played a significant role, as it became increasingly unattractive to grant special rights to university members compared to other groups such as craftsmen or merchants. At the same time, the ceremonial demotion of the university, as seen in rituals such as the funeral processions for the (craftsman) guilds, where the university members were given a position further back in the marching order, can also be interpreted as a conciliation meant to compensate the craftsmen for the loss of status that the city’s merchant class imposed on them during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The dispute over the privileged status of the university

With the Reformation, the university became subordinate to the Reformed city authorities in the statutes of 1532 and 1539. These statutes no longer referred to the papal privileges and the Letter of Freedoms from 1460. For its part, however, the university clung to its special status throughout the sixteenth century. In 1599, Rector Johann Jakob Grynäus, a professor of theology and the antistes of the city, made another attempt to regain the university’s old privileges and achieve completely independent jurisdiction over its own affairs. It seems foreign students had complained that the university in Basel was less independent than its peers. But even the initiative of Grynäus, no less than the city’s antistes and university’s rector, proved unsuccessful. Above all, it highlighted the difficult relationship between the university and the city’s authorities in the increasingly orthodox and absolutist Reformed state.

In 1634, during the Thirty Years’ War, an extraordinary tax was levied, with no exception for university members. Invoking their tax and customs exemption guaranteed in 1460 and pointing to fact that they were not represented in the City Council, the university resisted this imposition – without success.

Soon thereafter, in 1637, new disputes arose: the council established a new authority for moral oversight called the Reformation College, which was also intended to supervise the members of the university as burghers. In this case, Rector Remigius Faesch, a professor of law and son of Mayor Johann Rudolf Faesch, initially succeeded in preventing the university’s subordination to the city authorities. But just three years later, in 1640, conflicts broke out again.

“Around this time, the university had difficulties with the politicians, with powerful antipathies on both sides.”

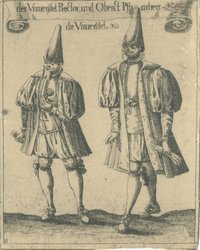

Now the professors were admonished to adhere to the dress code and “not to appear in long fashionable trousers, coats, and wide-brimmed hats.” In 1651, the meat tax was also levied on university members, from which the Letter of Freedoms had exempted them. The university Senate protested, pointing to German universities whose rights were restored after the Peace of Westphalia and were threatening to become competitors to Basel. But it lost on this matter in 1653.

In the following years, conflicts mainly revolved around jurisdiction, with a further escalation in 1656 on account of Theodor Wolleb, the professor of Greek and pastor of St. Martin’s Church. The City Council wanted to set an example and enforce its ban on holding ecclesiastical and academic offices simultaneously for everyone except the antistes. It therefore unexpectedly declared, explicitly and in reference to the statutes of 1532, that the old privileges of 1460 had already been abolished with that document.

“not as a successor to the papists”

Nevertheless, the university continued its resistance, commissioning in the rectorate year of Antistes Lukas Gernler (1659/60) the dean of theologians, Johann Rudolf Wettsein, to submit a new memoriale (a formal petition) to his father, the mayor. Accordingly, the anniversary year – celebrated here for the first time – was marred by conflicts, after even Wettstein failed to resolve the conflict. The dispute further escalated in 1668, when the deputies of the City Council admonished the faculty to not to consider themselves as successors of the papists, but instead to follow the statutes of 1532. Once again, the university insisted on the validity of its privileges from 1460, yet this only led to it being forbidden, under penalty, to present copies of the old privileges to the newly elected heads and deputies.

Ultimately, in 1671 a new oath of allegiance was introduced for burghers who were also members of the university, finally subordinating the institution to the legal-political structures of the absolutist state.

Loyalty and criticism

Despite all disputes over the autonomy and privileges of the university, along with questions about hierarchy and precedence within the faculty, as well as between professors and burghers, those at the university proved to be extremely loyal and obedient to city authorities during the political crises of the second half of the seventeenth century.

During the Peasants’ War of 1653, all foreign students remained in the city in support of its freedom and safety. After the bloody suppression of the rebellion, Theodor Wolder, a doctor of law from Königsberg, delivered a speech whose high ceremony reflected gravity of what had transpired, and the following year a master’s degree was awarded on the topic “De scelestissimo Rebellionis crimine” (On the most wicked crime of rebellion).

Even during the greatest crisis to have faced the city and its social structures, namely, the unrest of 1691, the majority of the university members sided with the old regime. That said, criticism within and of the university did exist. In a memoriale, the mathematician Jakob Bernoulli, at the time the most eminent scholar at the university, articulated his concerns in twenty points. They addressed the procedures for electing professors as well as the system of professorships in the Faculty of Liberal Arts, and the closely related issues of hierarchy and internal university promotion. Behind his criticism, it was easy to glimpse what amounted to ideas about a new form for the university. Bernoulli found himself compelled to apologize to the Senate but was later elected dean and rector without any troubles.