Legal equality. Equal opportunity? From the 1970s onward

Since the 1960s, the number of women students has increased significantly, and yet they remain disadvantaged in many ways. In the 1990s, policies to achieve equal opportunity began to take root at universities, aiming to make the legally anchored principle of equality more of a reality.

In 1977, Heinrich Tramèr from the Grand Council of Basel-City asked for an explanation for why the proportion of women in university faculty was only 3.8 percent; university institutes and departments were formally asked to respond. A wide range of opinions on women studying at the university was revealed. Some departments resorted to old, discriminatory views to explain their low percentage of women, suggesting that the “nature and suitability of women” determined the subject choices of women students. Others explicitly opposed such views. The physicists, for instance, responded by noting that the low percentage of women “may be due to the prejudice that physics and mathematics, as abstract and exact sciences, are harmful to the female psyche. The physicists at our institute do not believe in this prejudice.” Others pointed to gender-specific patterns of socialization . The historians, for example, noted that many decisions were made at home and in primary school, where girls were trained for their “typical” female roles as housewives and mothers.

Measurable and subtle disadvantages

A little over ten years later, Brigitte Studer wrote a report on the status of women at universities for the Swiss Science Council, identifying two notable trends for the situation both in Switzerland and abroad. The proportion of women students had doubled since the 1960s to about 40 percent – though with a significant delay in Switzerland compared to Europe and North America. Additionally, the discrepancy between “equality of access” and “equality of result” was evident. Although women had long had the same formal legal access as men, significant differences persisted in the distribution of subjects and degrees (horizontal segregation). Furthermore, the presence of women decreased sharply at higher hierarchical levels (vertical segregation): in 1985, 40 percent of those enrolled nationwide were women, but their share was only 32 percent of graduations, 20 percent of doctorates, and just 2 percent of professorships.

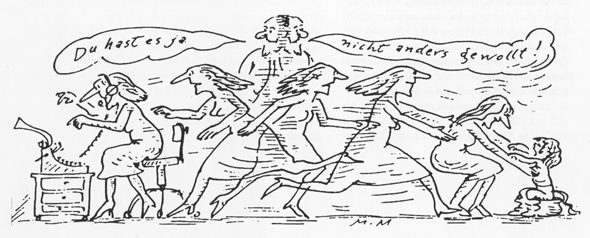

The fact that women are patently forced to overcome more discouraging hurdles during their studies and are less often encouraged in their scientific ambitions was also evident in a 1988 survey of female students in Basel. The qualitative study highlighted “hidden” inequalities left uncaptured by any statistics. “Women have to prove themselves twice over,” one student said, lamenting the latent higher pressure to demonstrate their abilities. Another pointed out the unequal chances of being noticed by professors and fellow students: “A woman has to repeat herself several times for people to pay attention, while a man is immediately heard.” When asked about possible advantages as a woman, a third student remarked resignedly: “To get what I want, I have to fight with the means that men accept in women, that is, I have to be charming and smile.”

Rights and opportunities

Equal rights does not yet mean equal opportunities. The ability to actually claim the rights legally due to all is unequally distributed, determined by social criteria such as class, gender, or ethnicity. This empirical fact is the reasons for demands to advance the equality of men and women, enshrined in the Swiss Federal Constitution in 1981, into forms of actual equality. As a political tool, it is primarily measures to promote women in traditionally male domains – such as universities – that have been proposed. The aim is to counteract the observed discrepancy between equal rights of access and unequal chances of success.

In Basel, gender equality policies were introduced into university institutions starting in the late 1980s. Under pressure from assistants and students, an ad hoc Senate commission “Women at the University” was established in 1988. It developed a list of proposals to improve the situation of women at the University of Basel, which were then adopted by the Senate on 19 December 1990. The key passage stated: “Women and men have equal opportunities in undergraduate and postgraduate studies, in appointments, and employment. The university authorities will implement suitable measures to ensure equal opportunities and promote women, particularly to increase the proportion of teaching staff who are women.

In 1991, the provisional Senate commission was made permanent. The report they presented in 1993 after five years of work was titled “How Nothing Is Achieved despite Clear Goals and Serious Efforts.” Following through on the university’s declared intention provoked resistance. In 1993, Basel-City’s Governing Council declined to financially support the establishment of a university daycare center and the position of a women’s representative.

Firm and binding

When the university was granted autonomy in 1996, the principle of equal opportunity and the tool of promoting women were incorporated into the objectives of the newly established University Act (Article 6) and the University Statute (Article 5). Since then, these principles have been a firm and binding part of the university’s legal foundation.

To implement this mandate for equality, the Office for Equal Opportunity was established in 1998. A particular focus of the office is on improving conditions for young women scholars and researchers. Since 2000, specific mentoring programs for different target groups have supported young women at all qualification levels (step!, Diss+, WIN, Frame Plus, Mentoring Deutschschweiz). Supporting women’s career advancement aims to address the enduring horizontal and vertical gender segregation in research and university life.