Academic collections and museums in Basel

Basel considers itself to be a city of museums, and a large number of these institutions belong to the university or are closely associated with it. These museums are university assets and have always been an important foundation for academic work in Basel. Starting with the oldest museum in Europe, what follows outlines the gradual process of differentiation that separated the various specialized museums of note in Basel – from the Amerbach Cabinet to the Schaulager.

As an enterprise dedicated to generating knowledge, science requires documentation even before analysis can begin, and one essential form of documentation is collecting – first of objects, and then of data. Usually, these collections are begun in ways that are largely unsystematic, i.e., not from any knowledge of the whole but primarily from an interest in what is special, extraordinary, curious, or rare. Secondary motives for collecting have been the desire for systemization and hence for organization, in addition to displaying and sharing what has been collected. Basel’s museum landscape is no exception here, having developed from individual “cabinets of wonders” to specialized collections.

Bonifacius and Basilius Amerbach and their collections

This history began in the chambers of humanist scholars, and especially that of the great Erasmus. After his death, his collection (books, pictures, coins and medals, honorary gifts, goblets, watches, and spoons) passed to his friend Bonfacius Amerbach, a professor of institutional doctrine and Roman law and five-time rector of the university. Around 1586, his son, Basilius Amerbach the Younger (1533–1591), like his father a professor of law, followed the customary practice of more sophisticated collectors in compiling an inventory of the more than 5,000 objects (including 2,000 drawings by old masters, with 100 works by Hans Holbein the Younger) that were stored in the privately owned house Zum Kaiserstuhl (located on the Rheingasse in Kleinbasel). Basilius A. thus created the famous Amerbach Cabinet, while also expanding its holdings with a large coin collection he had personally curated. Basilius furthermore initiated the excavation of the Roman theater in Augusta Raurica – an endeavor that is considered to be the first scientific excavation north of the Alps and thus the foundation of classical archeology.

When this collection was to be sold to Holland in 1661, the city, under Mayor Johann Rudolf Wettstein, argued that it be kept in Basel and made part of the university’s assets. A decade later, in 1671, it was made publicly accessible in the house Zur Mücke on Cathedral Square, where city residents could visit the collection every Sunday after the church service. Basel can thus lay claim to having Europe’s oldest museum sponsored by a civil authority.

Further growth in the size of the collection largely came about through donations of valuable private collections. As an example of such collections from the early days of this history, it is worth noting the fossils gifted in 1768 by the Muttenz pastor Hieronymus Annoni, as well as the Faesch collection, which was transferred to the university in 1823. From 1821 to 1849, the natural specimens were housed as a separate collection at Cathedral Square, at no. 11 in the Falkensteinerhof. The Faesch collection was created by the lawyer, university rector, and art collector Remigius Faesch (1595–1667) and represents a typical art cabinet from the seventeenth century. It was housed in the family residence at St. Peter’s Square and existed as a fideicommissum (a family estate entrusted in a fiduciary capacity) until 1823.

The split between Basel-City and Basel-Countryside

The split between the two Basels meant that the entire university was in jeopardy: the new canton of Basel-Countryside initially demanded a material division of the university’s property. The dispute was ultimately resolved by paying a settlement amounting to one half of a low appraised value. The experience of this threat, combined with a broader appreciation of the museum system, catalyzed a significant movement among Basel’s citizens, in close cooperation with the university, to found a Museum Society in 1841 with the purpose of constructing a new building, as well as a Museum Society of Volunteers (Freiwillige Museumsverein) in 1850. The dual purpose of this society was to support the collections, primarily through purchases, and to cultivate a sense of science and art among Basel’s citizens.

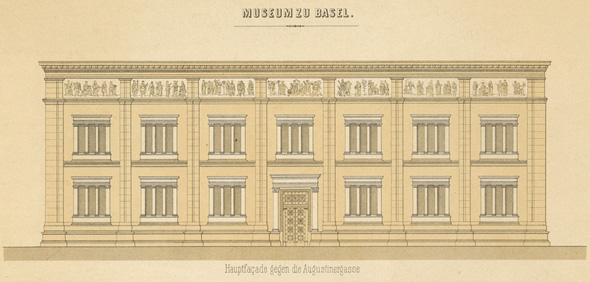

The next important milestone was the construction of the new, large museum building first envisioned in 1841, on the site of the former Augustinian monastery and Upper College, built according to the plans of Melchior Berri and ready for use in 1849. This new building allowed the collection to be separated out into different spaces first the first time, differentiating between art objects, casts of ancient sculptures, medieval urban artifacts, ethnographic/anthropological objects, natural history specimens, and a library. All of the collections were managed by volunteers or by professors under the overall responsibility of the Kuratel, a municipal oversight committee for the university. The only paid employees were the caretaker and the Sunday supervisors. In 1848, when the creation of a paid curator position was considered, Jacob Burckhardt was proposed as a candidate for the role, but some pushed back against what they considered to be an unnecessary position. Only a decade later was the decision made to establish a half-time position.

The choice of a late classicist style for the building reflected thoroughly antimedieval sentiments. Not only was the former Augustinian monastery ruthlessly eliminated, but a massive architectural cube was placed in the narrow alley that today appears out of proportion, as the medieval buildings on the opposite side were not removed as first envisioned. The intention was to construct a palace on this site with an unobstructed view of the Rhine, a modern version of the palaces built by medieval rulers; and the architect chosen, Melchior Berri, was ideally suited for the task. Berri was a member of the Grand Council and married to Jacob Burckhardt’s sister. He was also interested in obtaining a university professorship, though this never succeeded. He was trained in Karlsruhe, as one reads, “by the architectural will of the royal capital, guided so uniformly and with such discipline,” and driven by the vision that Basel needed for its “architectural education.” Even so, his preference would have been to secure a position at a “prominent court” rather than being merely a “republican architect.”

The museum building was meant to serve many purposes. This was true, first, in a practical sense, as the structure housed multiple collections, including a library with a librarian’s residence, a grand lecture hall, and even Schönbein’s chemical laboratory from Falkensteinerhof, albeit in the form of an amphitheater-style chemistry lab. But it was also true in symbolic sense. At the dedication ceremony, Professor Peter Merian declared the museum to be “vivid monument to the foresight that the authorities and citizens of Basel have brought to the interests of science and art in our time” – a promise that would ring true over the years. Figures placed in the foyer of the auditorium were further meant to symbolize the connections that bound both art and science to the city.

It was perhaps unexpected that, in the 1840s, Basel’s citizens preferred to erect a temple for its collections rather than creating much-needed space for university instruction. On Friedrich Mähly’s bird’s-eye view of Basel from 1847, the museum building, not yet completed, is rendered as a prominent colossal structure right in the center of the cityscape, while the old college building is inconspicuously situated along the edge of the Rhine. The other function of the new edifice was addressed by Professor Wilhelm Wackernagel: “In this museum, Basel has made a monument to itself.” That is to say, the building itself was meant to represent the entire city. Or as Othmar Birkner argues, it stood as a symbol for the tightly enclosed city as it had existed so far, while taking a defensive stance against the coming, unlimited world of traffic – as the counterpart, in a word, to the train station. Berri had designed the railroad gate incorporated into the city wall in 1844 (see Mähly’s bird’s-eye view of Basel), although he was unsuccessful in obtaining the commission to build the train station in 1854/55.

The central element of the building was the auditorium with a gilded coffered ceiling and the large gallery featuring equally sized portraits of 125 professors. Other universities (especially Tübingen) had similar galleries and likely served Berri as models. The portrait collection still hanging today in the auditorium and other rooms of the museum includes additional, older "conterfeit” portraits, some of which were created as early as the late seventeenth century. Among the images (all depicting men, of course), a number of likenesses were fashioned posthumously, i.e., retrospectively. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, for instance, Pope Pius II was honored as the university’s founding patron, while the cathedral provost Georg von Andlau was recognized as the university’s first rector. Writing about the university’s institutionalization, Paul Leonhard Ganz notes a need, during a period of obvious decline, to “glorify and perpetuate the reputation and dignity of a site shaped more by reforms than the Reformation.” Once started, this tradition was selectively continued during the twentieth century through governmental support of art.

Differentiation of the collection spaces

The steady growth of the collections eventually made it necessary to move the historical objects and copperplate engravings to secondary locations. In 1856, at the initiative of the Germanist Wilhelm Wackernagel, the historical collection was moved to the Bishop’s Court along with parts of the cathedral treasury. This marked the establishment of a precursor institution to the later Historical Museum, opened in 1894 and housed in the Barfüsserkirche (the former Franciscan church). Specific departments later acquired locations of their own, including the Kirschgarten Museum, the Musical Instrument Collection, and the Carriage and Sleigh Collection. One unique museum institution is the Swiss Museum of Pharmaceutical History on Totengässlein, created in 1924 from the collection of historical pharmacy equipment donated by Joseph Anton Häfliger, who taught courses on the history of pharmacy.

The collection of antiquities began early on in Basel, with items in public collections housed in both the Historical Museum and Art Museun. Yet it was only in 1966 that they received a site of their own in the Museun if Antiquities at St. Alban-Graben 5/7, following even more significant donations (from Giovanni Züst, Robert Käppeli, and René Clavel). This new institution was preceded by the Roman House, opened in 1957 in the former Augusta Raurica (in Augst in Basel-Countryside), and by the establishment of the Sculpture Hall in 1963 in an old factory building on Mittlerer Strasse (in the neighborhood of the Bernoullianum). The period in which originals were acquired was preceded by an interest in plaster casts of Greek and Roman masterpieces. Such reproductions were so highly regarded that the city was even willing to sell the original Golden Rose from the cathedral treasury, dating back to the fourteenth century, to Paris in order to acquire plaster casts with the proceeds of 805 Swiss francs. The sculpture collection, initially also housed in the main museum, was first relocated to an annex on Martinsgasse and then in 1887 to a side wing of the Kunsthalle (1872/85) in response to the painting department’s growing needs for space.

In 1910, at the instigation of Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer, the Swiss Museum of Volkskunde – an emerging field encompassing both ethnology and folklore – developed out of the Volkskunde department of the city museum, focused primarily on the “rural cultural heritage of the Swiss homeland.” First located in the museum attic, the collection has been housed in a special annex since 1953.

Running somewhat counter to efforts to increasingly regard the categories of nature and culture as interrelated, the two main collections of natural history and ethnology remain under the same roof but have now been further separated via two separate entrances. The Museum der Kulturen (Museum of Cultures), as the one side has now been called for some time, was given an extension designed by Herzog & De Meuron and completed in autumn 2010.

A new building for the Museum of Fine Art (Kunstmuseum)

Basel’s Public Art Collection remained at Augustinergasse for almost a century, finally receiving its own large exhibition space at St. Alban-Graben 16 only in 1936. While the first competitions were announced in 1909 and 1913, delays occurred for several reasons, including discussions about what the collections should hold; the lighting (side or overhead); funding; and, most notably (and protractedly), the location. Elisabethenschanze, Münsterplatz (Cathedral Square), and Schützenmatte were other sites under consideration. Unlike with the new college building, the removal of the venerable structure (the Württemberg Court) located at the new site provoked no resistance.

Yet after the jury finally decided in 1929 for Rudolf Christ’s proposal, a fierce controversy erupted over whether the requirements for the building’s use or aesthetics (with some pushing for a monumental building that would break from any bourgeois sensibilities) should be given more weight. As Dorothee Huber writes: “For the proponents of modernism, the insistence on the form of a palace to signal the building’s elevated purpose was an intolerable demonstration of power rooted in a conservative understanding of culture.”

In 1980, the Kunstmuseum was expanded to include the Museum für Gegenwartskunst (Museum of Contemporary Art), a separate building funded by philanthropist Maja Sacher and designed by architects Wilfrid and Katharine Steib, in a former paper factory at St. Alban-Rheinweg 58/60. The space was dedicated to art produced after 1960 and was intended, in particular, to hold the collection created in 1933 by the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation. This branch of the museum underwent an indirect expansion in 2003 with the Schaulager in Münchenstein, again designed by Herzog & De Meuron. Funded by the Laurenz Foundation (created in 1999 by Maja Oeri), the Schaulager is a hybrid of a public museum, art storage facility, and institute for art research. With the acquisition of the former National Bank building at St. Alban-Graben 8, the foundation additionally provided a generous home for the university’s Department of Art History and its library, while also opening up new space for the Kunstmuseum. A direct extension to the Kunstmuseum was built on the neighboring Burghof site, again largely with private funding