The Voluntary Academic Society (Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft, FAG)

The Voluntary Academic Society (Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft, FAG) was founded on 17 September 1835 with the primary goal of preserving the university. This support was particularly crucial in the wake of the 1833 cantonal separation, which had significantly constrained the city’s capacity to sustain the institution. The society’s core mission, both then and now, centers on providing material support to the university through contributions to buildings, institute equipment, expansion of museum collections and the university library, research projects, scientific publications, and faculty salaries.

Alongside this concrete objective, the society harbored from its inception a less tangible aim, first articulated in the statutes of 17 September 1835: “to promote scientific education in general." This aspiration predated the cantonal separation, having been initially recorded on 5 March 1833, when there was no apparent need for rescue efforts. At that time, the goal was framed as “to inspire our audience with a greater interest in science and to encourage active participation in the well-being of our educational institutions.” This encompassed intentions to exert an “instructive influence” and offer “popular lectures.” The aim reflects the growing significance – and recognition thereof – of science among the educated bourgeoisie, a trend evident in Basel during the 1830s, independent of the cantonal separation issue. Consequently, the society's inaugural financial support in September 1835 funded two public lecture series. The Bernoullianum, inaugurated in 1874 and largely financed by the FAG, exemplified this commitment. This university building for the natural sciences included a spacious 450-seat lecture hall for public presentations, superseding the ground floor of the Augustinermuseum, which had become inadequate for scientific demonstrations.

The ideal of civic associations

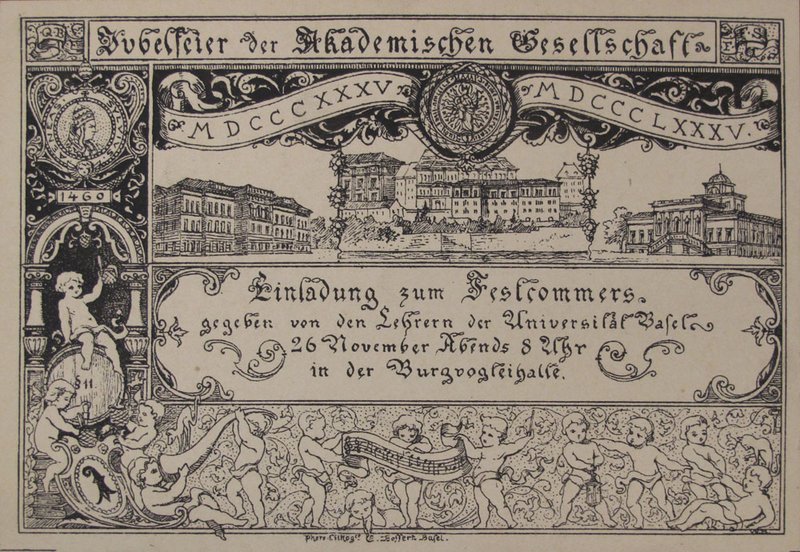

The initiative was also founded on the general ideal of civic associations, which had grown in importance since the 1820s. The aim was “to gain strength through this union, whose individual elements had so far been almost ineffective” (first appeal of 5 March 1833). The idea that support from independent private associations is a key component of modern societies remained a guiding principle. The 1860 annual report of the FAG notes: “In the spirit of our time, a new foundation for such efforts has been recognized in the free union of like-minded individuals. We see powerful associations for material interests or those deeply engaging the masses for religious purposes; why should it not also apply to scientific and scholarly endeavors?” A core group formed in 1866 was described, somewhat exaggeratedly but highlighting the claim to public service, as “composed of all ages, classes, professions, and views, as Basel then contained.” A small play from 1885 also took up this theme, proclaiming in the final verses: “Not one hand alone, but all the hands / United of all classes / To support, to maintain, / What was held equally high by young and old alike – indeed, / Today, joyfully, in pure jubilation / Let us join the chorus!” (on the occasion of 26 November 1885, by Paul Reber). A volume published in honor of the society in 1885 noted that the “idea of association and the union of many to achieve great, common goals” had become a commonplace in recent decades. The private nature of the new association was made even more meaningful by the painful fact that the university's assets had been unfairly included in the division of cantonal property, and it was assumed that an FAG would not be exposed to such political risks.

The decision of the Grand Council on 9 April 1835 to preserve the university despite the financial crisis caused by the cantonal separation encouraged the initiators of the future FAG to support the authorities “through the voluntary cooperation of well-meaning citizens.” The core group consisted of three councillors, Andreas Heusler, Peter Merian, and Christoph Burckhardt, the first two of whom were professors at the university, as well as high school principal D. LaRoche. Another important founding member was theology professor Wilhelm Martin de Wette, who had already thrice served as rector (1823, 1829, 1834) and was a member of the influential Board of Education from 1829 to 1837.

Now the issue of the separation had become central to the argument for the society: the founding appeal of 20 April 1838 envisioned that the university might “survive the destructive storms that have so deeply shaken our commonwealth and caused it so many wounds.” The aim was to compensate for material loss with additional intellectual effort; the hope was that Basel might “strive, especially at this moment, to replace what has been taken from it in terms of territory and material means by developing intellectual activity and strength.”

On 17 September 1835, the society was officially constituted, with Andreas Heusler-Ryhner appointed chair; he is rightfully described in the literature as the primary initiator of this creation. Heusler-Ryhiner held the position with great dedication for thirty-three years (until his death in 1868). In its founding year, the society had ninety-six members. No mere club for social activities, it limited its events to the rather sparsely attended annual meetings.

Until 1854, membership remained around this level. For unknown reasons, the number of members saw a significant increase from 169 to 595 in the years 1864/65. In 1866, an unsuccessful attempt was made to use the reorganization of the university to attract more members. The highest number in the first 100 years was reached in the jubilee year of 1885 with 839 members; another peak was around the university’s anniversary in 1910 with some 670 members. Today, the FAG has around 1,300 members.

Material and political assistance

Besides funding the two lecture series noted above, the initial contributions included support for a professor’s salary and acquisitions for the collections. An example of commitment to salary issues occurred in 1849, when the FAG guaranteed Daniel Schenkel, professor of systematic theology, compensation until he secured another position, should the university be closed (!). In the inaugural annual report, the chairman noted: “For this reason, our society was founded. It did not conceal that its initial efforts would be small and modest; but it had faith in the future, and this faith was based on trust in the communal spirit of our fellow citizens, on the conviction that sincere efforts for higher human goods would also be blessed from above.” Equally vital as the material contributions was the political support from the FAG, particularly in 1850/51, when the abolition of the university was debated, and during 1854–1864, when the project of a national Swiss university threatened the status of the University of Basel.

The university and the city owe many significant buildings to the FAG. These include the Bernoullianum in 1874, the Pathological Institute in 1880, the Vesalianum in 1885, the University Library in 1896, the expansion of the Pathological-Anatomical institute in 1901, and the Institute of Chemistry in 1910. However, regarding the university building project, it’s noteworthy that around half of the construction costs (400,000 of the 817,450 Swiss francs) were contributed by the FAG, and the project was only approved by the state after this private support was secured. The 400,000 Swiss francs could never have been paid out of the FAG’s assets. The FAG’s contribution lay in its ability to secure several patrons to fund the project, primarily the brothers Adolf and Alfred Merian, who donated 100,000 Swiss francs in memory of their brother, Prof. J.J. Merian. The collection raised another approximately 250,000 Swiss francs, leaving “only” about 50,000 Swiss francs to be spread over four years and charged to the current contributions.

During its major development, a shift in donations occurred: while support for construction dominated in the second half of the nineteenth century, later support in the area of remuneration gained prominence. FAG chair Heinrich Iselin-Weber observed that the state was increasingly able to assume construction tasks through taxation of cantonal residents, while the ever-advancing differentiation of science continually resulted in new teaching areas and assignments requiring consideration.

The history of gifts and bequests paints an impressive picture of Basel’s tradition of patronage, documented in detail in the literature. Two special fundraising campaigns merit particular mention. The first is the Anniversary Foundation for the Promotion of Scientific Research in the Humanities, established for the 1935 anniversary. This campaign addressed the paradoxical fact that the humanities were often underfunded precisely due to their modest needs. In 1943, a dedicated fund with the same purpose was created and funded through a collection. Another significant event was the university’s 500th anniversary in 1960, which led to a joint fundraising campaign with the Basel Chamber of Commerce. The resulting Fund for Teaching and Research raised over ten million Swiss francs (at that time’s value), with six million Swiss francs coming from Basel’s four chemical companies at the time.

A representative spectrum of activities, also detailed in the annual reports, is provided by the 1985 anniversary prospectus: research grants for studies in dermatology, archaeology, and psychiatry, contributions to ethnological research expeditions, grants for equipment for the ENT clinic, the Department of Surgery, and the Mineralogical-Petrographical Institute, contributions for collection acquisitions for the Museum of Ethnology, the Egyptological Seminar, the Natural History Museum, and several publication grants.

In 1985, the FAG’s anniversary gift involved funding a visiting professorship for an outstanding international scholar each year for ten years, with each faculty taking turns hosting the professor for one semester. The series commenced in summer 1986 with the internationally renowned sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf. At the regular general meeting on 18 September 1985, held exceptionally in the Grand Council Hall, former Government Councillor and Director of Education Arnold Schneider delivered a keynote speech on “The University of Basel and the political context in the years1955–1985.” In 2010, the FAG celebrated its 175th anniversary and supported the university in numerous projects, such as the Basel Homer Commentary and the endowed assistant professorship for the SNF project eikones.